Biology and Management of the Lesser Chestnut Weevil in Michigan Chestnut Orchards

DOWNLOADJune 27, 2024 - Maximillian Ferguson, Michigan State University Department of Entomology, and Deborah McCullough, Michigan State University Departments of Forestry and Entomology

Introduction

Michigan is the leading producer of commercial chestnuts in North America, providing chestnuts for fresh consumption, along with gluten-free flour, chips for brewing beer and many more products. In a recent survey, more than 50% of U.S. chestnut growers reported demand consistently exceeds their annual harvest. Given that most (90%) chestnuts consumed in the U.S. are imported from China and Europe, Michigan growers have ample opportunity to expand production to meet increasing domestic demands.

In recent years, an increasing number of Michigan chestnut producers have experienced serious damage from the lesser chestnut weevil (Curculio sayi Gyllenhal). This native insect likely evolved with American chestnut (Castanea dentata) but is now an important pest in chestnut orchards in many eastern states.

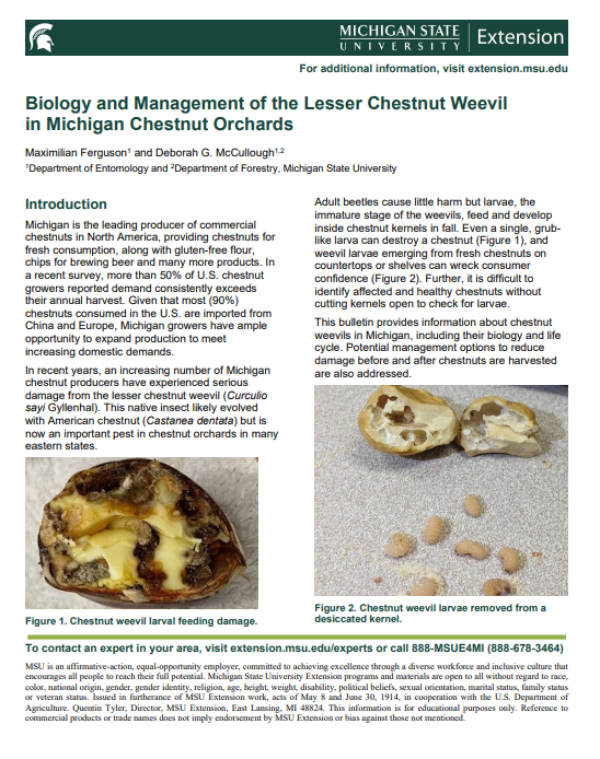

Adult beetles cause little harm but larvae, the immature stage of the weevils, feed and develop inside chestnut kernels in fall. Even a single, grub-like larva can destroy a chestnut (Figure 1), and weevil larvae emerging from fresh chestnuts on countertops or shelves can wreck consumer confidence (Figure 2). Further, it is difficult to identify affected and healthy chestnuts without cutting kernels open to check for larvae.

This bulletin provides information about chestnut weevils in Michigan, including their biology and life cycle. Potential management options to reduce damage before and after chestnuts are harvested are also addressed.

Life Cycle

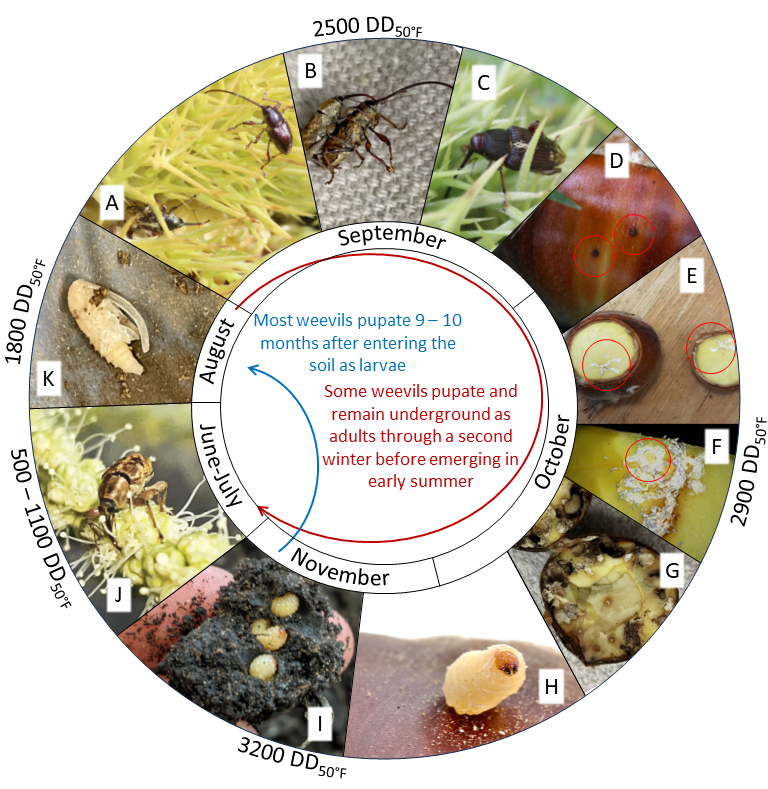

Chestnut weevil adults congregate and mate on burs in September (Figure 3), corresponding to approximately 2,500 cumulative degree-days (DD) using a threshold temperature of 50 degrees Fahrenheit (DD50F).

Adult female weevils use their specialized mouthparts at the end of their long snout to chew a hole through the bur and shell of the chestnut into the kernel. This leaves small black bruises on the shell of the nut (Figure 4C-D).

After feeding, the females pivot, extend their ovipositor into the hole in the kernel then lay several eggs just inside the shell of the nut (Figure 4E-F; Figure 5). These eggs hatch in one to two weeks and the white or cream-colored larvae (Figure 2) feed on the kernel for approximately five weeks (Figure 4G). Mature larvae chew circular exit holes through the shell of the nut (Figure 4H) then drop to the ground and burrow into soil. If nuts have already been harvested, however, larvae will still chew an exit hole and emerge from the nuts. Once larvae are in the soil, they construct smooth-walled pupal chambers (Figure 4I) where they will remain for several months. Most larvae will pupate the following fall (Figure 4K) then emerge from the ground as adults, coinciding with bur and kernel development. A portion of the weevils, however, remain underground through a second winter. These insects will pupate and emerge from the soil as adults the following year in late spring or early summer, typically congregating on blooming catkins (Figure 4J). This two-phased underground diapause (dormant period) results in a biennial cycle of weevil density in orchards, with high and low populations occurring in alternate years. In Michigan, weevil populations are consistently higher in odd years compared to even years.

Monitoring Adult Weevils

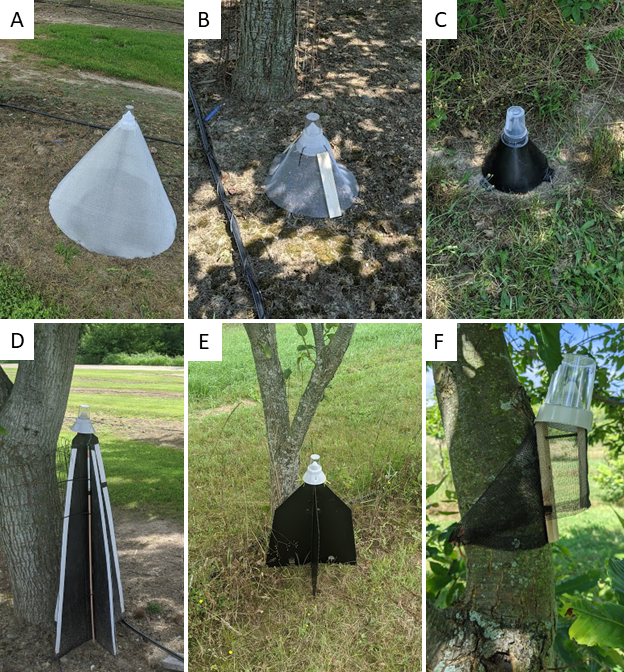

Homemade and commercial traps to monitor emergence or activity of adult chestnut weevils (Figure 6) are available. There are no commercially available lures to attract weevils to the traps, however, and none of the traps are highly effective at capturing adults.

A rough estimate of current weevil densities can be attained using a simple limb tapping technique. Spread a large sheet, tarp or drop cloth beneath the canopy so that the edge of the cloth is just outside the longest branches. Shake or strike branches over the drop cloth with a long pole or stick. When adult weevils are disturbed, they drop from the canopy and play possum (feigning death) for a few moments. These weevils can be easily captured and counted. Weevils tend to congregate and may not be uniformly distributed within an orchard. Sampling two to four aspects of at least 5 to 10 trees per acre should provide a good indication of the current weevil population in the orchard.

Damage

High or even moderate densities of chestnut weevils can become a serious problem within commercial orchards. Unmanaged weevil populations can infest more than 60% of harvested chestnuts and a few growers have reported losing 90% of their harvest due to weevil feeding. Larval feeding along with the frass excreted by larvae inside chestnut kernels renders the nuts foul and unmarketable (Figure 1). It can be even more problematic if larvae emerge after consumers have purchased fresh chestnuts (Figure 7). Weevil larvae crawling across a marketplace shelf or a countertop can ruin the appeal of fresh chestnuts for consumption or future purchases.

Pre-Harvest Weevil Management

Adult weevils are most abundant and active in fall after burs mature and kernels have completed development. However, they can be found in orchards throughout the growing season. In our studies in Michigan, 4% of weevils were captured before catkin bloom (mid-May – late June; approx. 150 – 800 DD50F), 8% were captured during catkin bloom (late June – mid-July; approx. 800 – 1,300 DD50F), 15% were captured as burs developed after catkin bloom was completed (mid-July – late September; approx. 1,300 – 2,500 DD50F), while 73% were captured after kernel development was completed in fall (late September; approx. 2,500 DD50F).

Timing cover sprays of insecticides is an essential aspect of controlling adult weevils. Most insecticide labels encourage applicators to avoid insecticide applications when trees are blooming (late June – mid-July; approx. 800 – 1,300 DD50F) to minimize potential harm to pollinators. Although chestnut trees are wind pollinated, chestnut catkins attract an array of pollinators. Insecticide sprays to control chestnut weevil adults can be applied in early to mid-September (approx. 2,200 DD50F). At this point, most adult weevils have emerged from the soil to mate and lay eggs in mature burs and kernels. Always read pesticide labels and be mindful of pre-harvest intervals before making an application.

Many Michigan orchards have been invaded by Asian chestnut gall wasp (Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu), another serious pest that can affect chestnut trees and reduce yield. A parasitoid wasp, Torymus sinensis (Kamijo), is a critically important natural enemy of Asian chestnut gall wasp. When applying an insecticide cover spray to chestnut trees in Michigan, avoid applications during the flight period of Torymus sinensis (Kamijo) (late May – early July; approx. 300 – 1,000 DD50F). See Michigan State University Extension bulletin E3457 (https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/asian-chestnut-gall-wasp-e3457) for more information on Asian chestnut gall wasp and T. sinensis.

Post-Harvest Weevil Management

It is important to treat harvested chestnuts to stop development of weevil larvae inside the kernel as quickly as possible. Two options for post-harvest control can significantly reduce numbers of weevil larvae developing and emerging from harvested chestnuts: water curing and hot water submersion. Water curing is a simple treatment that was traditionally used to kill weevils and other pests in harvested chestnuts. This process involves submerging chestnuts in room temperature water and allowing a partial lactic fermentation process to occur over the course of 7 to 9 days. After submersion, chestnuts can be dried for several hours then refrigerated until sold. This treatment requires no expensive equipment and can be a practical tactic for hobbyists and small producers. We performed this treatment, for example, using standard 30-gallon ice chests (Figure 8).

Hot water submersion is a faster, more effective, and more efficient option for controlling weevil larvae in harvested chestnuts. Chestnuts must be submerged in water heated to 120 F (49 C) for 15 to 20 minutes then allowed to dry at room temperature, before they are moved into cold storage. Large commercial operations often use a commercial vegetable blancher or similar piece of equipment to treat pounds of chestnuts at one time. Hobbyists can use a sous vide (Figure 9) or an outdoor burner to treat smaller batches of chestnuts.

It is essential that nuts reach an internal temperature of 119.6 F (48.7 C). This ensures that more than 99% of larvae will be killed. Size of nuts affects how rapidly internal temperatures increase during submergence. Chestnuts larger than 1 inch in diameter, for example, should be submerged for 15 to 20 minutes while smaller chestnuts need to be submerged for 10 to 15 minutes. Use a thermometer and probe to periodically check water temperatures and internal temperatures of nuts from each batch to ensure consistency.

Managing chestnut weevils in commercial orchards is increasingly a challenge for Michigan growers and processors. There is minimal allowance for pest presence in the market due to the grub-like appearance of the larvae and high degree of damage caused by larval feeding. Growers can use properly timed insecticide sprays to reduce adult densities and egg laying, while processors can use post-harvest treatments to kill weevil eggs and young larvae before they cause noticeable damage to nuts. Combined efforts on both fronts can minimize chestnut weevil problems and help Michigan’s thriving chestnut industry continue to expand.

Print

Print Email

Email