Michigan chestnut crop report for the week of August 29, 2024

The optimal control window for chestnut weevil is imminent in much of the state.

Weather review

Over the last month, most areas of Michigan have seen average temperatures for this time of year. The exception was early this week when the heat index reached over 107 degrees Fahrenheit in some areas of the state. On Aug. 27 we saw major windstorms across the state and rapid temperature declines. Accumulated precipitation was less than average last week but slightly above average over the last three months.

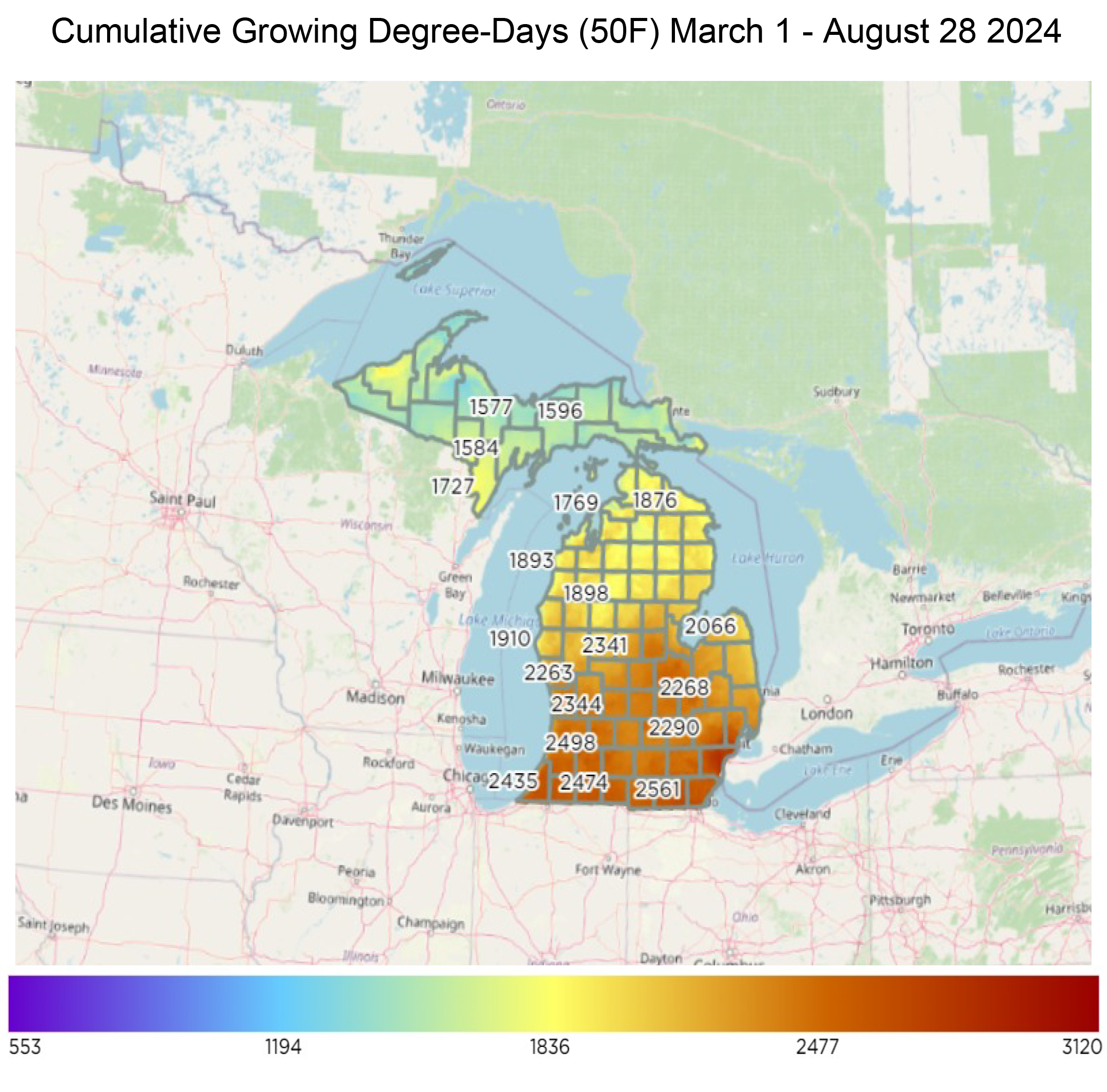

For the Lower Peninsula, growing degree days (base 50) range from the mid-1500s in the Upper Peninsula to nearly 2,500 in southern Michigan. This equates to a couple days to 14 days ahead of normal for most of the lower peninsula. Most areas of the Upper Peninsula are below normal or closer to average.

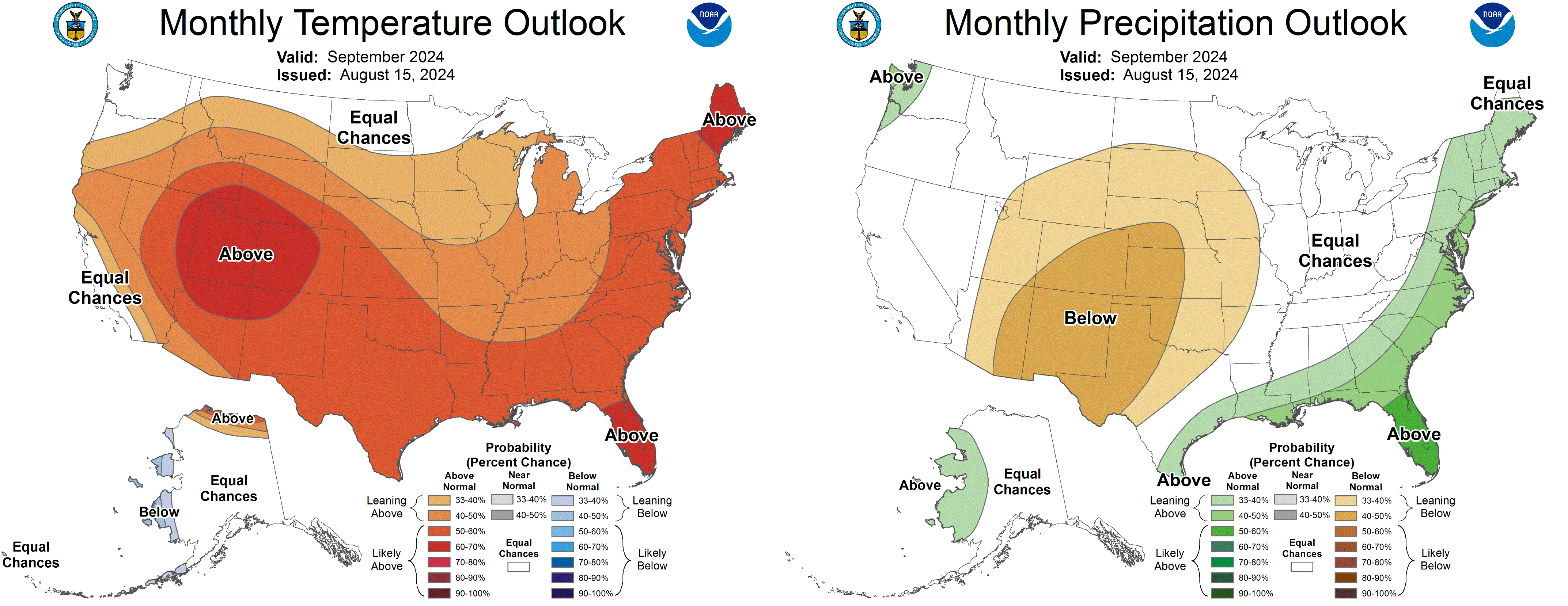

Looking ahead

Medium range guidance suggests a chance for slightly below normal temperatures September 2-6 but then above average temperatures through September. The 6-10 day forecast suggests drier than normal conditions.

See the most recent Michigan State University agriculture weather forecast.

Management activities

Crop estimation

It is very important for chestnut growers to accurately estimate the crop each year, as this is the start of the process of setting prices. Even though chestnuts are a fall crop, market negotiations start as early as August, particularly in years with large crops. To estimate the yield in Michigan, we must consider tree age, type and weather events when we evaluate how large the yield might be. For example, if there was frost in the spring or a harsh winter we would expect to see reduced yields. Droughts, excessive rain, pollination weather and excessive heat may also factor into the yield.

When considering the type of trees, we are primarily delineating based on whether the trees are seedlings or cultivars. Seedling trees are genetic individuals with high levels of variability making the crop load of seedling trees much more difficult to estimate. Conversely, cultivars are genetically identical making their performance more predictable and uniform. Each cultivar is different and requires that we estimate them separately, for example the cultivars Colossal and Labor Day would require separate crop load estimates and then be extrapolated proportionally based on their representation in each orchard. For those of you with primarily Colossal and a couple other cultivars, the estimation is much simpler and should be more accurate. Experience and speed of crop load estimation improves quickly with practice.

Protocol

To estimate crop load, first estimate the number of nuts per bur and then estimate the number of burs per tree. These estimates should be performed for each cultivar and age group, as applicable.

To estimate the nuts, open five burs from five trees of each cultivar and age. Be sure to sample from all sides and reachable heights of the tree. Normally, there will be one or two nuts in a bur, sometimes three. Add up the total number of nuts you observed and divide it by the number of burs to estimate the number of nuts per bur. For example, if you looked at five burs on five 8-year-old Colossal trees (25 burs total) and counted 45 nuts, then you would divide 45 nuts by 25 burs, which equals 1.8 nuts per bur on average. Perhaps your 12-year-old Colossal trees had more nuts and averaged 1.9 nuts per bur.

To estimate burs, divide the tree into four quadrants (north, south, east and west) to help improve accuracy. Then count the number of burs on the end of each branch within each quadrant on five trees. Again, trees of differing age should be measured separately. The number of burs on five trees in each age and cultivar class and divide by five to determine the average bur count per tree. For example, if the five trees you evaluate contain 112, 126, 108, 100 and 145 burs per tree, then the average burs per tree equals 591 burs per five trees, which equals 118.2 burs per tree. Consider using a small handheld click counter to assist you.

To extrapolate crop load from the nut and bur estimations use the following formula:

(Nuts per bur x burs per tree x number of trees in class) ÷ nuts per pound* = crop load lbs.

*To complete this formula, you need to know how many nuts per pound to expect. Generally, Colossal can have about 20-30 nuts per pound, so for our purposes we could average that out to 25 nuts per pound. Nuts per pound is part of the estimation that has the potential to cause errors. If the nuts are smaller (30 nuts per pound), you will have fewer pounds. If larger (18 nuts per pound), you will have more pounds. If trees have been shaded in some areas of the orchard, there will be fewer burs and if you have full sun, you might have more burs in some areas.

For the examples we have created above, let’s do the math:

(1.8 nuts/bur x 118 burs/tree x 50 trees) ÷ 25 nuts/pound = 424.8 pounds of nuts on the 8-year-old Colossal trees in this example.

Again, this would have to be repeated for each cultivar and age class and then added together to get the farm total.

To get an accurate estimate on seedlings, you must estimate each tree separately. The pounds from a group of seedling trees may range from 0 to 60 pounds depending on the age, history and weather.

Timing

The earlier we can make an estimate the better, but it is often difficult to determine how many nuts are developing in the bur. The earlier burrs are opened, the harder it is to accurately count the number of nuts in a bur. Growers can practice their estimate in mid-August and then recheck them for accuracy in early-mid September.

Insect pests

The following is a summary of current pest related information for Michigan chestnut orchards. For more detailed information and additional images, please visit the pest management section on the MSU Extension Chestnuts website.

Chestnut weevil activity is ramping up and some areas of the state are approaching the treatment window for this pest. Recent MSU research has revealed that the critical control window for this pest occurs in September, but it is still important to scout now. To learn more about it, check out the new publication: Biology and management of the lesser chestnut weevil in Michigan orchards.

In recent years, an increasing number of Michigan chestnut producers have experienced serious damage from the lesser chestnut weevil (Curculio sayi Gyllenhal). This native insect likely evolved with American chestnut but is now an important pest in chestnut orchards in many eastern states.

Adult beetles cause little harm but larvae, the immature stage of the weevils, feed and develop inside chestnut kernels in fall. Even a single, grub-like larva can destroy a chestnut, and weevil larvae emerging from fresh chestnuts on countertops or shelves can wreck consumer confidence. Further, it is difficult to identify affected and healthy chestnuts without cutting kernels open to check for larvae.

Chestnut weevil adults congregate and mate on burs in September, corresponding to approximately 2,500 cumulative degree-days (DD) using a threshold temperature of 50 degrees Fahrenheit (DD50F). Adult female weevils use their specialized mouthparts at the end of their long snout to chew a hole through the bur and shell of the chestnut into the kernel. This leaves small black bruises on the shell of the nut.

After feeding, the females pivot, extend their ovipositor into the hole in the kernel then lay several eggs just inside the shell of the nut. These eggs hatch in one to two weeks and the white or cream-colored larvae feed on the kernel for approximately five weeks. Mature larvae chew circular exit holes through the shell of the nut then drop to the ground and burrow into soil. If nuts have already been harvested, however, larvae will still chew an exit hole and emerge from the nuts. Once larvae are in the soil, they construct smooth-walled pupal chambers where they will remain for several months. Most larvae will pupate the following fall then emerge from the ground as adults, coinciding with bur and kernel development. A portion of the weevils, however, remain underground through a second winter. These insects will pupate and emerge from the soil as adults the following year in late spring or early summer, typically congregating on blooming catkins. This two-phased underground diapause (dormant period) results in a biennial cycle of weevil density in orchards, with high and low populations occurring in alternate years. In Michigan, weevil populations have been higher in odd years compared to even years.

Homemade and commercial traps to monitor emergence or activity of adult chestnut weevils are available. There are no commercially available lures to attract weevils to the traps, however, and none of the traps are highly effective at capturing adults. A rough estimate of current weevil densities can be attained using a simple limb tapping technique. Spread a large sheet, tarp or drop cloth beneath the canopy so that the edge of the cloth is just outside the longest branches. Shake or strike branches over the drop cloth with a long pole or stick. When adult weevils are disturbed, they drop from the canopy and play possum (feigning death) for a few moments. These weevils can be easily captured and counted. Weevils tend to congregate and may not be uniformly distributed within an orchard. Sampling two to four aspects of at least five to 10 trees per acre should provide a good indication of the current weevil population in the orchard.

Adult weevils are most abundant and active in chestnut orchards in the fall after burs mature and kernels have completed development. However, they can be found in orchards throughout the growing season. In our studies in Michigan, 4% of weevils were captured before catkin bloom (mid-May – late June; approximately 150 – 800 DD50F), 8% were captured during catkin bloom (late June – mid-July; approximately 800 – 1,300 DD50F), 15% were captured as burs developed after catkin bloom was completed (mid-July – late September; approximately 1,300 – 2,500 DD50F), while 73% were captured after kernel development was completed in fall (late September; approximately 2,500 DD50F).

Timing cover sprays of insecticides is an essential aspect of controlling adult weevils. Most insecticide labels encourage applicators to avoid insecticide applications when trees are blooming to minimize potential harm to pollinators. Although chestnut trees are wind pollinated, chestnut catkins attract an array of pollinators. Insecticide sprays to control chestnut weevil adults can be applied in early to mid-September (approximately 2,200 DD50F). At this point, most adult weevils have emerged from the soil to mate and lay eggs in mature burs and kernels. Always read pesticide labels and be mindful of pre-harvest intervals before making an application.

|

Selected Pesticides for Chestnut Weevil Management, 2024 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Active Ingredient (IRAC Code) |

Products Labeled |

Pesticide Efficacy1 |

Beneficial Insect Toxicity2 |

Notes |

||||

|

PLH |

Scarabs |

Plum curculio |

Bees |

Mite preds |

Insect preds |

|||

|

Phosmet (1B) |

Imidan 70-W |

G-E |

E |

E |

T |

S |

M |

Phosmet is an organophosphate insecticide and provides good broad-spectrum control of many pests in Michigan. |

|

Carbaryl (1A) |

Carbaryl 4L, Sevin XLR Plus, Sevin SL |

E |

G-E |

G |

T |

T |

T |

Carbaryl is an organophosphate insecticide and provides good broad-spectrum control of many pests in Michigan. |

|

Acetamiprid(4A) |

Anarchy 30SG, Anarchy 70WP, ArVida 30SG, Assail 30SG, Assail 70WP, Azomar, Intruder Max 70WP, Tristar 8.5SL, Quasar 8.5SL |

E |

E |

E |

M |

S |

M |

Targets aphids, leafhoppers, leafminers, Japanese beetle, plum curculio, as well as some lepidopteran pests. This translaminar (locally systemic) material has a long residual inside the plant. |

|

Clothianidin(4A) |

Belay |

E |

E |

E |

M |

S |

M |

Targets aphids, leafhoppers, leafminers, curculio, Japanese beetle and lepidopteran pests. As a foliar spray Belay is a translaminar (locally systemic) material, and has long residual inside the plant. |

|

1. Pesticide efficacy ratings; E-excellent, G-good, F-fair, P-poor, U-unknown, N-pest not included on label. 2. Beneficial insect toxicity; S-safe, M-moderate, T-toxic, U-unknown, not evaluated on chestnut. |

||||||||

|

Pesticide efficacy and beneficial insect toxicity is based on trials in fruit crops with products containing the same active ingredient, as reported in the E154 Fruit Management Guide, Michigan State University Extension. |

||||||||

Asian chestnut gall wasp female adult flight takes place from approximately 1,050 to 2,100 cumulative growing degree days (GDD), using a threshold temperature of 50 degrees Fahrenheit (GDD50F) and a starting date of January 1. In Michigan, this typically corresponds to late June or early July and extends until mid-August. According to current degree day accumulations, adult flight has likely ended in Michigan chestnut orchards with known infestation (central and southern Michigan). However, chestnut growers in counties west of Highway 127, especially areas south of I-96 in lower Michigan, should be carefully scouting their trees for evidence of the Asian chestnut gall wasp during the growing season and again in fall or winter, after leaf drop. These areas are at increased risk as they are adjacent to or within the areas known to be infested at this time.

In late spring and summer, green or reddish galls can be observed on branches or leaves. In fall and winter, look for dried, brown galls on the shoots. Many old galls remain on the tree through winter and are more visible after leaves drop in fall. These old galls can remain attached to the trees for at least one or two years after the wasps have emerged.

Asian chestnut gall wasp produces one generation per year and is a parthenogenetic species, meaning all wasps are female and reproduction occurs asexually. Thus, even a single wasp can start a new infestation. Gall wasp adults are very small, about 1/8-inch (3 mm) long, and have black bodies with yellow legs. Adult wasps lay eggs inside chestnut buds over a four- to six-week period, typically from the last week of June to the second week in August in southwest Michigan. This period corresponds to approximately 1,050 to 2,100 cumulative growing degree days (GDD), using a threshold temperature of 50 F (GDD50F) and a starting date of Jan. 1. Eggs hatch after about 40 days. The tiny larvae, which cannot be seen without magnification, remain dormant in the buds throughout the winter until the following spring.

Growers with young trees should carefully monitor for Asian chestnut gall wasp adult flight and consider applying a pyrethroid insecticide for control. Young trees are particularly susceptible to severe damage by Asian chestnut gall wasp due to the limited number of buds and the need to establish tree structure during the first years of establishment. Growers can hang yellow sticky traps in mid-late June in the canopy to passively trap for adult flight and better time pesticide applications. Growers with mature trees should monitor the impact of Asian chestnut gall wasp on yield and tree health and make management decisions accordingly.

For more information, check out the Asian Chestnut Gall Wasp bulletin.

Japanese beetle adults are still out and feeding. Japanese beetle adults are considered a generalist pest and affect many crops found on or near grassy areas, particularly irrigated turf. Adult Japanese beetle emerges around early July and feeds on hundreds of different plant species, skeletonizing the tissue. If populations are high, they can remove all the green leaf material from the plants.

There are no established treatment thresholds or data on how much Japanese beetle damage a healthy chestnut tree can sustain, but consider that well-established and vigorous orchards will likely not require 100% protection. Younger orchards with limited leaf area will need to be managed more aggressively.

For more information on Japanese beetle, check out the pest management section of the chestnut webpage. For a list of registered insecticide for use in Michigan chestnuts, refer to the Michigan Chestnut Management Guide.

Potato leafhopper numbers are high this year, likely due to their early arrival. Like many plants, chestnuts are sensitive to the saliva of the potato leaf hopper which is injected by the insect while feeding. Damage to leaf tissue can cause reduced photosynthesis, which can impact production and quality and damage the tree. Most injury occurs on new tissue on shoot terminals with potato leafhopper feeding near the edges of the leaves using piercing-sucking mouthparts. Symptoms of feeding appear as whitish dots arranged in triangular shapes near the edges. Heavily damaged leaves are cupped with brown and yellowed edges and eventually drop from the tree. Severely infested shoots produce small, bunched leaves with reduced photosynthetic capacity.

Adult leafhoppers are pale to bright green and about 1/8 inch long. Adults are easily noticeable, jumping, flying or running when agitated. The nymphs (immature leafhoppers) are pale green and have no wings but are very similar in form to the adults. Potato leafhopper move in all directions when disturbed, unlike some leafhoppers which have a distinct pattern of movement. The potato leafhopper can’t survive Michigan’s winter and survives in the Gulf States until adults migrate north in the spring on storm systems.

Scouting should be performed weekly as soon as leaf tissue is present to ensure early detection and prevent injury. More frequent spot checks should be done following rainstorms which carry the first populations north. For every acre of orchard, select 5 trees to examine and inspect the leaves on 3 shoots per tree (15 shoots per acre). The easiest way to observe potato leafhopper is by flipping the shoots or leaves over and looking for adults and nymphs on the underside of leaves. Pay special attention to succulent new leaves on the terminals of branches.

For more information on insecticides available for the treatment of potato leafhopper refer to the Michigan Chestnut Management Guide.

In 2022 and 2023, some growers reported higher than typical European red mite populations, so everyone should be on the lookout as early as possible. European red mites overwinter as eggs in bark crevices and bud scales and are the most commonly observed species in Michigan chestnut orchards. Eggs are small spheres, about the size of the head of a pin with a single stipe or hair that protrudes from the top (this is not always visible). Eggs can be viewed with a hand lens or the naked eye once you have established what you are looking for.

Scout for overwintering eggs and early nymph activity in the spring to assess population levels in the coming season. As temperatures warm, overwintering eggs hatch and nymphs move onto the emerging leaves and start feeding. Adult European red mite are red in color and have hairs that give them a spikey appearance. Adult and nymph feeding occurs primarily on the upper surface of the leaves. This first generation is the slowest of the season and typically takes a full three weeks to develop and reproduce. This slow development is due to the direct link between temperature and mite development. Summer generations, favored by the hot and dry weather, can complete their lifecycles much faster with as little as 10 days between generations under ideal conditions.

As you scout, remember that not all mites are bad. Consider documenting the levels of predacious mites in your orchard. If healthy populations of mite predators exist, they will continue to feed on plant parasitic eggs and nymphs and can be an effective component of your mite management program. Predaceous mites are smaller than adult European red mite and twospotted spider mite, but they can be seen with a hand lens and typically move very quickly across leaf surfaces.

Mite control starts with monitoring early in the spring looking for the overwintering eggs (European red mite) and assessing the mite pressure. Ideally, growers will be using limited insecticides with miticidal activity in their season long programs, as that protects their beneficial mite populations which help minimize pest mites. If pest mite populations are high enough to require control, superior oil application when the trees are dormant is an effective method of treatment. If issues with mites arise during the growing season, refer to the Michigan Chestnut Management Guide for control options.

Disease

Growers should not be pruning chestnuts at this time as they are vulnerable to infection by not just chestnut blight but the oak wilt fungus as well.

Existing chestnut blight infections (caused by Cryphonectria parasitica) can be observed at this time. There are no commercially available treatments for chestnut blight. Growers may prune out infected branches or cull whole trees as needed to limit disease pressure. Infested material should be burned or buried to further limit inoculum spread. To learn more about chestnut blight, visit the pest management section of the chestnut webpage.

Stay connected

For more information on chestnut production, visit www.chestnuts.msu.edu, sign up to receive our newsletter and join us for the free 2024 MSU Chestnut Growers Chat Series.

If you are unsure of what is causing symptoms in the field, you can submit a sample to MSU Plant & Pest Diagnostics. Visit the webpage for specific information about how to collect, package, ship and image plant samples for diagnosis. If you have any doubt about what or how to collect a good sample, please contact the lab at 517-432-0988 or pestid@msu.edu.

Become a licensed pesticide applicator

All growers utilizing pesticide can benefit from getting their license, even if not legally required. Understanding pesticides and the associated regulations can help growers protect themselves, others and the environment. Michigan Pesticide Applicator Certification is administered by the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. You can read all about the process by visiting the Pesticide FAQ webpage. Michigan State University offers a number of resources to assist people pursuing their license, including an online study/continuing educational course and study manuals.

This work is supported by the Crop Protection and Pest Management Program [grant no 2021-70006-35450] from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Print

Print Email

Email