Recreational fishing isn’t just about fun, it also provides food

Harvesting local, wild-caught fish is one of the benefits of fishing. Each year, Michigan anglers fishing under a recreational license harvest fish worth over $40 million from Great Lakes waters alone.

Fishing isn’t always easy, but sometimes everything comes together for the perfect trip. If you are at the right place at the right time with the right bait, it can be very gratifying. I had one of those days this fall. Salmon were just starting to make their way from Lake Michigan into river mouth areas, which can make for excellent fishing or a lot of frustration.

At this time of year salmon stop actively feeding on baitfish, although they do occasionally bite out of aggression, curiosity, or habit. On some days you will see dozens of salmon jumping and splashing while they ignore every lure and bait that passes by. At other times there may be no sign of fish, but your first cast results in a jolting strike.

It was my good fortune to have that happen on that one magical trip. In fact, I hooked into another salmon on my second cast, as well. After a few riotous hours of drag-peeling runs, three-foot fish jumping clear out of the water, and trying to avoid getting tangled in my own line as hooked fish attempted to dart between my legs, I decided to call it an evening after hooking six salmon and landing four.

Sure, I could have stayed and enjoyed several more hours of some of the best salmon fishing I’ve experienced, but the night was not yet complete for other reasons. These fish were fresh from Lake Michigan— mostly silver and still high in fat content. One was a female full of eggs. I bled each of the fish to help improve the quality of the meat, as well, and now it was time to get the fish onto ice in the cooler bag in my car and head home to process fish.

For me, and for many other people, fishing isn’t just about the fun of catching fish. Much of the satisfaction comes from from properly cleaning, preserving, and preparing the fish to provide healthy, delicious food for family and friends (yes, and myself as well!). After filleting the salmon, cutting fillets into portion-sized pieces, vacuum-sealing some to freeze, preparing two different brines to soak other pieces for smoking, cutting and curing egg skeins to use for bait later, and preparing a meal of bang bang salmon for the family, I finally called it a night.

How do we value recreational fisheries?

In my time working for Michigan Sea Grant, I have been involved in a few projects related to the economics of fishing. Most have focused on demonstrating the (substantial) economic impacts of people traveling to pursue fishing as a recreational activity. For tourism to generate economic impacts in a community, people must travel and spend money. This is one way to look at things, but it considers the angler only as a consumer, ignoring the importance of fishing to the angler who saves money by fishing close to home.

When we talk about the value that fishing provides to society, we are really limiting our frame of reference if we view fishing only as an outdoor pastime akin to golf or hiking. In tourism studies, these other forms of recreation are considered “substitution behaviors” that anglers would engage in if fishing wasn’t available. I would argue that only hunting, gathering, and perhaps gardening would potentially qualify as substitutions for fishing for one simple reason: They all provide food.

Returning to the salmon fishing example, an economic impact study would have ignored the substantial economic benefits provided by procuring fresh, local fish for my family. Before being cleaned, the total weight of Chinook salmon caught was 61 pounds. Fillet yield for Chinook salmon is 0.55, which means that I harvested roughly 35.55 pounds of fillets that evening. If you were to buy Chinook salmon harvested from the Great Lakes, you would pay $18 per pound through one of the few online retailers that offers the option. Wild Alaskan Chinook is a much more expensive substitute, while farmed salmon or other less desirable species can be less expensive. Still, using Great Lakes fish prices as a reference suggests that I offset my grocery costs by $639.90 with a few hours of fishing.

You might think that salmon is an exceptionally expensive, but Great Lakes panfish command even higher retail prices. Great Lakes bluegill fillets sell for $24.95/lb. and yellow perch retail for as high as $32.50/lb. Although coldwater salmon and trout certainly get a lot of attention from Great Lake anglers, warmer bays and connecting waters like Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River offer fantastic fishing for panfish and gamefish like walleye, pike, bass, and catfish.

Everyone is aware of the rising price of groceries over the past few years, and seafood is no exception. In most households, store-bought seafood is not a staple food. It is reserved for special occasions, entertaining company, or perhaps consumed in larger quantities by those who are health conscious and have the means to afford it. The average household income for frequent seafood buyers is $26,000 higher than that of people who never buy seafood. The average price per pound of seafood at the grocery store is now over three times that of chicken or pork. In May 2024, Circana found that the retail price of seafood was $9.43/lb.—quite a bit lower than prices for most Great Lakes fish.

In Michigan, we put a high premium on the fish species we can catch in local waters. It is part of our regional culture, and likely stems from the experiences many of us connect to the act of catching and harvesting fish for personal use. When I lived in Mississippi, this was very evident. Few people knew what a walleye was, and walleye were not available at supermarkets or restaurants. Instead, catfish were the fish of choice for rich and poor alike.

One could make the argument that a cheaper substitute, like farm-raised tilapia, could serve as the basis for determining grocery cost offsets from harvesting Great Lakes fish under a recreational fishing license, but I would argue that our regionally available species command a high price precisely because of their unique contribution to our shared outdoor heritage in the Great Lakes state.

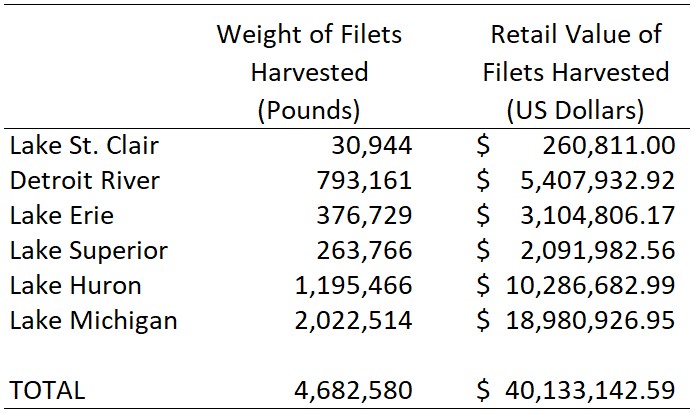

Retail value of fillets harvested by Great Lakes anglers in Michigan

With the help of folks with Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR), I determined the total weight of fish fillets harvested by anglers fishing under a recreational fishing license in Michigan waters of the Great Lakes. Creel surveys conducted by DNR staff served as the starting point, since these surveys are used to calculate the number and weight of fish harvested.

Published yields for different species were then used to determine the weight of fillets. When published values were not available, the yield of another species of similar shape was used as a surrogate (e.g., bluegill for pumpkinseed sunfish) or determined by a colleague with extensive experience in fish processing. Finally, retail cost of skin-on fillets of Great Lakes species was determined by searching online. When multiple vendors offered the same species at different prices, the average price was used. Surrogate species were used for comparable species in some cases (e.g., Chinook salmon for coho, channel catfish for bullhead).

All told, anglers fishing under recreational fishing licenses in Michigan harvest over 4.6 million pounds of fillets worth over $40 million from the Great Lakes on an annual basis (see Table 1). This doesn’t include the harvest of fish from inland lakes and rivers, either. When you consider that roughly 70% of trips taken by Michigan anglers are taken on inland waters, it is clear that the $40 million figure is only the tip of the iceberg.

Considering that there were roughly 1.18 million licensed recreational anglers in Michigan in 2023, we could divide the total fillet value by the number of licenses and say that the average Michigan angler harvests $33.90 worth of Great Lakes fillets per year. This seems like a good place to start in terms of demonstrating the value of food procured through recreational fishing in Michigan, but it does not tell the whole story. Inland fisheries are likely to contribute even more to offsetting the cost of buying seafood at retail prices. Inland fisheries are also generally, but not always, less expensive to access.

Fishing beyond fun

Salmon fishing in river mouths provides one low-cost option for tapping into the abundance of our Great Lakes fisheries, but there are plenty of others. Shore anglers in Michigan have a wealth of options for low-cost access, from piers and public parks to state and national forest land. Even so, a lack of publicly accessible shoreline is an issue in some areas.

A new effort is underway to shine a light on “Fishing Beyond Fun,” which aims to focus more research attention on shore fishing for Great Lakes species. Eventually, this may lead to a more comprehensive understanding of gaps in access. The effort should also improve our understanding of the benefits that fishing provides, not only in terms of food value but also in terms of mental health and strengthening community, cultural, and family ties.

Recreational angling provides over $40 million in fish fillets for anglers each year. Most probably don’t think too much about the dollar value, though. The experience of harvesting food from local waters gives us a sense of connection to our environment and sharing that food with loved ones completes a cycle that is as old as humanity itself.

References and notes on calculations

Harvest estimates

Total number of fish harvested under recreational fishing licenses was provided by Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Zhenming Su provided harvest estimates generated through creel surveys conducted in Lake Michigan, Lake Superior, Lake Huron, Lake Erie, and Detroit River in 2022, with expansion calculations used to account for ports that were not surveyed in 2022. Creel estimates were not available for Lake St. Clair in 2022, so harvest estimates from 2021 creel surveys were used for Lake St. Clair. Christopher Kemp (DNR) provided harvest estimates from charter fishing on Great Lakes waters in 2022.

The number of fish harvested in both charter and non-charter fisheries was multiplied by the average weight for each species to estimate biomass harvested. In most cases, the average weight of fish harvested was available for 2022 for individual management units within each lake for commonly harvested species. For fish species that were not as commonly harvested, lakewide average weight was used. Average weights of fish harvested from Lake St. Clair were not available, so average weights from other Great Lakes were used for biomass calculation. For additional details on harvest estimation see references below.

- Su, Z., Clapp, D., 2013. Evaluation of Sample Design and Estimation Methods for Great Lakes Angler Surveys. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 142, 234-246

- Su, Z., He, J., 2013. Analysis of Lake Huron recreational fisheries data using models dealing with excessive zeros. Fisheries Research 148, 81– 89.

Fillet yields

The yield for each species was determined using references below when possible. When yield was not available in published references, a surrogate species of similar shape was used (e.g., bluegill was used as a surrogate for pumpkinseed). Yield was multiplied by biomass harvested to generate an estimate of the weight of skin-on fillets harvested for each species.

- Estimation of Daily Per Capita Fish Consumption of Alabama Anglers

- Pacific Seafood Recoveries and Yields

- Production of Walleye as a Potential Food Fish

- Fillet Weight and Fillet Yield

- Burbot May Look Odd but it Can be Tasty

Online retail price of Great Lakes fish

Websites below were accessed in July 2024 to assess the online price of Great Lakes fish fillets. Whenever possible, the price of frozen skin-on fillets from fish caught in Great Lakes waters and sold by U.S. retailers was used. When multiple vendors offered the same species, an average value was calculated. Northern pike and burbot were not available from U.S. retailers, so Canadian retail price was converted into U.S. dollars. Burbot were harvested in Lake Eire, but pike was harvested from other Canadian waters. When prices were not available for a species, a surrogate species of similar value was used (e.g., lake whitefish was used as a surrogate for round whitefish).

- MI Great Lakes Fish Company

- Oceanside Seafood

- Whyte’s Fishery & Smokehouse

- Walleye Direct

- Steelhead Food Company

Michigan angler survey

A statewide survey of licensed Michigan anglers found that 28.6% of fishing trips were taken on Great Lakes waters. The same survey found that the most common “favorite fish to eat” was perch (27.0%), followed by walleye (22.2%). Salmonines also ranked highly, with 17.1% of anglers listing some type of salmon or trout as their favorite fish to eat.

- Lupi, F., 2004, A profile of recreational anglers in Michigan. Agricultural Economics Staff Paper 04-17, Department of Agricultural Economics, Michigan State University, East Lansing.

Seafood trends

Articles from Seafood Source provided information on seafood price and consumer trends. According to Circana data cited in one article, as of March 2024, the average price per pound for seafood was $9.43 while chicken averaged $3.07 and pork averaged $3.14. The second article cited a 2024 Food Industry Association report that found that 37% of those surveyed indicated that they were cutting back on seafood purchases due to inflation and the high cost of seafood. A similar 2023 report found that frequent seafood buyers had an average household income of $89,000 vs. $63,000 for those who never bought seafood.

- Seafood is getting cheaper but US consumers still aren’t biting

- Inflation hurt seafood sales in 2023, but home prep gaining traction

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research, and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University and its MSU Extension, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 34 university-based programs.

This report was prepared by Michigan Sea Grant under award NA22OAR4170084 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce through the Regents of the University of Michigan. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, or the Regents of the University of Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email