MSU researcher leading Great Lakes sea lamprey eradication project

Helping to prevent both the decline of native fish populations and negative impacts on the fishing industry

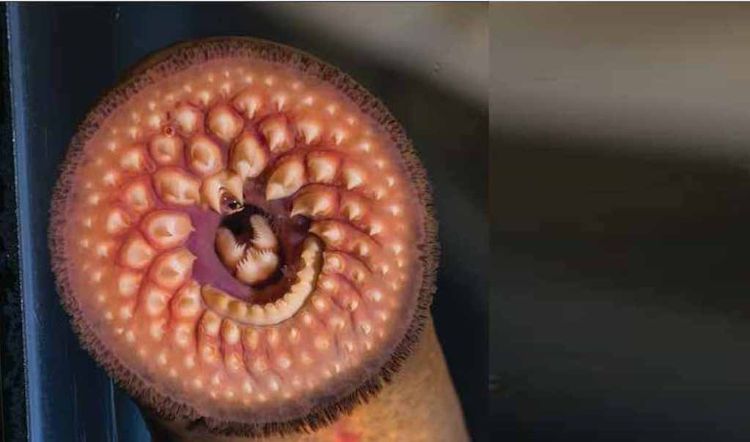

Sea lamprey devastated the Great Lakes fishery in the mid 20th century, contributing to the decline of native fish populations and hurting a multi-billion-dollar fishing industry.

Michigan State University researcher Michael Wagner and a team of scientists from the Great Lakes Fisheries Commission (GLFC) are looking at biological and behavioral research, and agricultural technology techniques to continue to control these invasive species. According to the GLFC, “when control is relaxed for even a short time, sea lamprey bounce back and can inflict major harm. Elevated sea lamprey abundances take years to remedy and higher populations set back fishery and ecosystem recovery by decades.”

“Our goal is to manipulate the (sea lamprey) movements in order to create circumstances that allow our control program to become more targeted,” Wagner said. “We have a big initiative that was the brainchild of Andrew Muir, the science director for GLFC.

“The plan is to develop a selective fish passage device, which is essentially a biological filter that prevents sea lamprey from passing through while allowing other fish to do so, which has never been attempted before, let alone achieved.”

The project leaders hope to secure the connections of the rivers that flow into the Great Lakes, while also preventing the damage caused by the invasive sea lamprey. Sea lampreys spend a significant portion of their lives in tributaries as larvae, so sea lamprey control begins when biologists assess tributaries to determine which ones contain larval sea lampreys. The goal then is to eradicate those populations before they can reach the lakes.

“There's a great deal of interest -- ecologically, economically and culturally -- in reconnecting the rivers of the Great Lakes to the lakes by allowing the organisms to move from river to lake, and back, while still blocking invasive species. And our goal is to find a way, through manipulation of sea lamprey predator/prey dynamics and other behavioral characteristics, to create a fish-pass device that will enable the fishes that we want to pass into the river and block or capture the ones we don’t, such as lamprey.”

Wagner’s research focuses on the behavioral ecology of fishes and addresses migration strategies, search behavior, habitat selection and anti-predator behavior.

“We have to begin to view these fish as decision makers that will react to specific circumstances, and we must try to create circumstances they've evolved to recognize,” he said. “Once we get a grasp on the cognitive framework of the animal, we can combine machines that recognize what type of fish is trying to get through with this understanding of what types of conditions would equate to ‘yes, come this way’ or ‘no, don't go that way.’”

Wagner serves on the science advisory board for the project, which is commissioned through the Environmental Protection Agency and is funded by the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. Construction of a novel passage device is underway and Wagner expects its completion by early 2022.

“After that we will be embarking on intensive research to try to get to the point where we can achieve this selected passage and shift this program into an operational facility instead of an experimental one,” he said.

While the work is aimed at resolving an immediate issue for the Great Lakes, the process the team uses lays the groundwork for the future.

“This project is an amazing crucible to figure out how to solve really difficult problems. It's multi-jurisdictional; there are two nations, multiple states and provinces at play in here that require discovery of new ways for governments to work together. It is a rich tapestry of different cultures, the value of the rivers and the lakes in different ways that have to be negotiated,” he said.

Wagner generally focuses on the development of practical, scientifically sound and innovative management tools to control invasive species and to help manage fish populations.

“I decided early on I wanted my work to have a meaningful impact on people's lives, and in a way in which those people have the opportunity to help define what that impact should be, which is fancy way of saying that I want to work on things that are important to science, as well as important in nature,” he said.

“In the case of the sea lamprey work, I would like to find a way for these groups to control the organism in a way that is least harmful to the ecosystem and best supports what the culture wants from the ecosystem. As a representative of Michigan State University, I want to honor the state’s investment by helping us solve problems in the ways that our stakeholders feel they should be solved.”

Print

Print Email

Email