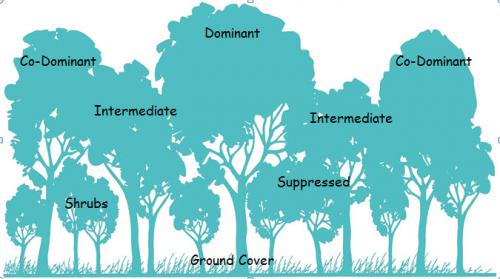

Layers of the forest

Recognizing and managing for vertical structure can enhance forest productivity and diversity

Many find that taking a walk through the woods is a refreshing and rejuvenating experience. We give many reasons for feeling this way in the woods: birdsong, fresh air, filtered sunlight, wildflowers, rustling leaves, etc. Though it seems obvious that trees are the dominant players in these areas, their growth and arrangement across the landscape has a significant impact on the other features we consider important to a ‘forest.’ One way to begin recognizing this is to pay attention to a forest’s vertical structure. Standing inside, how far can you see through the trees? Are there young trees and shrubs interrupting the view? Looking up, are there saplings growing under the main canopy of treetops? How much sunlight is peeking through the canopy and reaching the forest floor? All the levels, or layers, that make up the forest from bottom (including soil) to the treetops define its vertical structure.

Foresters have some general terminology for these different layers. Carpeting the ground at the lowest level, the leaf litter serves as a critical nutrient “factory” where a host of invertebrates (insects, worms, fungi, bacteria, etc.) work to break down the trees’ cast offs (leaves and other organic litter) into component elements that eventually are re-absorbed by the forest’s plant communities. The next layer includes all the annual and perennial herbaceous plants and woody debris. This can include the so-called spring ephemerals—wildflowers that take advantage of spring sunlight by blooming before the overhead trees fully leaf out. This layer can also include multiple species of ferns, sedges and grasses, as well as tree seedlings that are just emerging and establishing themselves.

Above this ground cover layer, the woody plants predominate. The lowest layer typically contains woody shrubs and older seedlings. These are typically called “suppressed” because they receive little to no direct sunlight if the forest’s canopy is fully developed above. Some species have evolved to subsist entirely on filtered sunlight, while other seedlings and saplings can only survive for a period of time before they will need an opening in the canopy to grow into a mature tree. Those trees that are lucky enough to push through a sunny opening in the canopy are at the “intermediate” layer, but may only receive direct sunlight on the top of the trees’ crown. Then there are the trees whose crowns make up the majority of the forest’s canopy, “co-dominating” the majority of the available direct sunlight. Additionally, some individuals—either because of an early start, fast growth and/or a remnant of earlier disturbances—may tower over the average canopy height in a more “dominant” position, receiving full sunlight for a large proportion of its crown.

Why are all these layers important? Every plant species has adapted to fill a niche: taking advantage of the sunlight, temperature, soils and companion organisms in unique ways. Each species evolved ways to take advantage of those resources to survive, thrive and reproduce. Generally speaking, overall forest productivity is better with more forest layers. This in turn allows for a greater set of opportunities for various animal species. For example, different bird species require different layers for their habitat. Some migratory species, such as red-eyed vireos and yellow warblers, need those suppressed layers, while others like ovenbirds or hermit thrushes need dense ground cover for nesting. Trees that inhabit those different layers are also critical for overall forest stability. If and when a disturbance such as wind, disease and even fire kills a few or all of the trees in the canopy, the suppressed trees will be ready and waiting to fill that gap.

Diverse layering in a forest can be encouraged in mature forests by encouraging occasional gaps in the canopy through single-tree or group selection harvesting techniques. The best approaches for these strategies are dependent on a variety of factors, such as soil composition and drainage, potential wildlife browsing, existing tree species, etc. A consulting forester is a trained professional who can help forest owners determine what is best for personal goals and the land itself. For more information on how to find a forester near you, consider contacting your local Conservation District or Michigan State University Extension county office.

Print

Print Email

Email