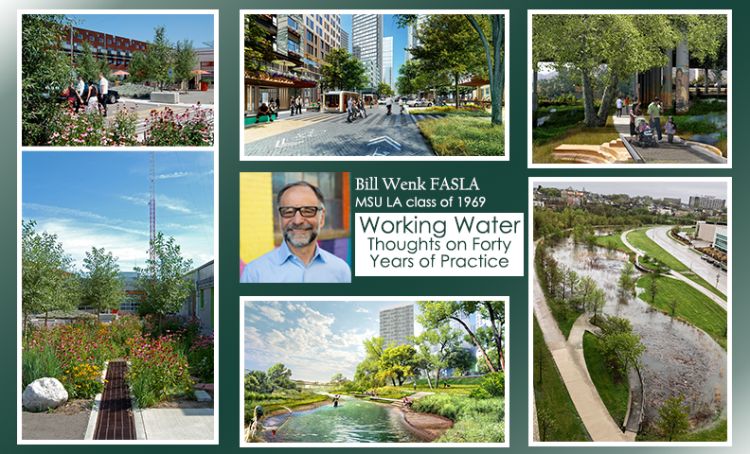

LandTexture: Working Water - Thoughts on Forty Years of Practice

Better approaches of managing and designing stormwater infrastructure in ways that support more efficient water use, clean urban runoff, support natural systems, and enhance the vitality and livability of our cities.

I was well trained in the traditional art, craft, and technical skills that a young landscape architect needed in 1969 when I received my undergraduate degree from Michigan State. Ian McHarg’s book Design With Nature had just been published. The environmental and social principles and concepts that formed the foundation of McHarg’s book, really a manifesto, inspired me then and is still the basis for much of my firm’s work.

For 40 years, Wenk Associates, the firm I founded in 1982, has been creating projects that illustrate how McHarg’s broad concepts of environmentally responsible landscape planning can be realized using the traditional skills of site and landscape design that I learned as a student at Michigan State. This article summarizes the primary messages of Working Water: Reinventing the Storm Drain, a book I wrote last year, and published by ORO Editions. The book demonstrates better approaches of managing and designing stormwater infrastructure in ways that support more efficient water use, clean urban runoff, support natural systems, and enhance the vitality and livability of our cities.

The book includes three parts. The first part is a teaching tool that describes basic concepts of stormwater management for students and the interested public. The second part is a monograph describing selected projects of the firm and their value as civic and natural resources in addition to their essential function of stormwater control. The projects included are at site, community, and watershed scales. Each project integrates multifunctional landscapes that support economic opportunity and stronger communities by creating places for gathering, recreation and leisure, and provide a connection to nature. The third part is a resource manual describing lessons-learned after decades of observing project successes and failures and ways to overcome legal, financial, and institutional barriers to implementing green infrastructure at a district scale.

The Best Projects Improve the Health and Vitality of Natural and Human Environments

There are four primary aspects to our best projects:

1) Landscapes Should Provide Multiple Functions

Landscapes that create the greatest value are those that are designed to do more than one thing. Multifunctional landscapes are most effective as part of critical infrastructure when they improve the economic, civic, and natural qualities and functions of a community. It is our responsibility as landscape architects to understand the principles behind the engineering and science of stormwater management, natural sciences, and other urban systems to fully realize their potential.

2) Traditional Design Principles and Practices Are an Important Part of Creating Healthy Human and Natural Environments

The traditional art and craft of landscape architecture that I learned as an undergraduate at Michigan State gave me the tools that we as landscape architects need to fully realize the civic and recreational values and the multifunctional potential of urban infrastructure. As landscape architects we have the skills to integrate beauty and function in ways that most other professions lack. Our challenge is to move beyond practicing at a site or project scale to positively influence the urban systems that give form to our cities and implement at system, watershed, and regional scales.

3) Beauty and Human Scale Are as Important as Multiple Functions

Beauty and function are not mutually exclusive. In fact, some of the most beautiful objects are often the most functional objects, pared down to the essentials and exquisitely adapted to their use or function. The first part of the book provides examples of ingenious preindustrial humanly scaled urban water systems that are used in multiple ways and are fertile ground for research as inspiration for our professional work today. These systems possessed a simple functional beauty and enhanced the livability of the communities they served.

4) The Best Projects Are Scalable - from Site to District to Community to Watershed

The most successful and valuable design solutions are those that can be implemented at multiple scales. Most valuable are site scale projects that can easily be scaled up to form an integrated and linked system that works at a district, watershed, or regional scale. The components of the system should improve the functional value of infrastructure and enhance natural and human needs to be of the greatest value.

Healthier Communities, Healthier Natural Systems

The second part of Working Water describes and illustrates selected Wenk Associates’ projects that range in scale from a small stormwater garden at one of the firm’s offices in Denver to master planning the revitalization and restoration of the Los Angeles River corridor as it passes through the city of Los Angeles.

The following selected projects represent different scales, from site to system to watershed.

TAXI Mixed Use Development - Beauty and Function at a Site and Small System Scale

The redevelopment of a vacant taxi dispatch center built over an abandoned landfill along the South Platte River in an aging Denver industrial district provided an opportunity to rethink the site’s challenging stormwater infrastructure issues. The essentially flat existing terrain made drainage difficult and potentially costly to build a conventional stormwater system, and the surface parking that would cover much of the site was a requirement to keep the project affordable. To minimize costs and to take full advantage of the site’s infrastructure, multiple-benefit solutions to the challenges were identified through a site plan that integrates parking, pedestrian spaces, and landscape areas into a surface stormwater system.

The green infrastructure approach to stormwater management provided multiple benefits: 1) it eliminated the need to import fill material (which would have been required to create positive drainage for a traditional piped system), as well as almost all subsurface storm pipe, contributing to significant cost reductions; and 2) the stormwater that would be captured and infiltrated would support the desired landscape, which brings the natural qualities of the nearby river into the site.

Today, TAXI is a 25-acre urban village, a home and workplace for artists, architects, designers, and “creative class” business startups, with a café, daycare, and gathering areas integrated into groves and meadows sustained by the site’s stormwater system. The redevelopment integrates a functional stormwater system into traditional landscapes that serves multiple functions. TAXI Illustrates how beauty and function can be integrated as a localized system that incorporates and links a series of site scale stormwater gardens, swales and infiltration basins and other green infrastructure techniques.

(Left) The use of low-cost native plants, seeded native grasses, painted pedestrian walkways integrated into access drives, and the use of green infrastructure as the primary means of stormwater management supports a walkable environment. This approach significantly reduced site development costs.

(Right) Covered surface channels, grass swales, and stormwater infiltration gardens convey and treat runoff from adjacent buildings and parking areas, eliminating the need for costly subsurface storm pipes and curb and gutter.

The next project illustrates how an industrial district can be designed at a larger scale to integrate public and private stormwater systems.

Menomonee Valley Redevelopment - Multi-Functional Landscapes at a System Scale

One of our firm’s most significant projects is the adaptive reuse of a 150-acre heavily polluted and flood-prone industrial district and railyard along the channelized and degraded Menomonee River in the heart of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The design brief for the project required that reuse of the district create living wage jobs, access to nature and recreation, and cleaner water for the nearby neighborhoods.

The concept that our firm developed as winner of as national competition, struck a balance between creation of job-rich, living wage light industrial manufacturing, recreation for underserved nearby neighborhoods with trail connections to adjacent neighborhoods, and river and natural area rehabilitation. Light industrial areas and recreational uses were organized around a series of multifunctional naturalized southern Wisconsin landscapes that manage flooding and filter storm runoff, creating a more vibrant community with greater access to nature.

The project creates integrated natural and urban systems at a district scale, possibly the most important scale that we as a profession can act to address some of the pressing environmental, equity, and social issues of our time.

(Above) Aerial view of the Community Park stormwater treatment thirteen years after construction and a four-inch rainstorm. Visible are four different landscape types. (Photo credit: Paul Boersma)

The River Mile – A Proposed Ultra Urban District Integrated with a Restored River

Through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Denver grew rapidly and the area along the South Platte River in central Denver became an important industrial center and railyard, and most recently, an amusement park. As a result, the river was channelized and lost its natural qualities and multiple environmental challenges remain due to the area’s industrial past.

The River Mile, a proposed 60-acre urban district will replace the amusement park and embrace the river as a place for community gathering and an important component of a district-wide stormwater management system. The site lies entirely within the hundred-year floodplain. Future improvements will require the floodplain to be contained within the river channel and will create the opportunity to reconstruct the channel as a functioning natural floodplain and community amenity. Lined with urban parks and a pedestrian promenade, the river will define the district’s identity as the central gathering place for leisure and civic activities.

The reconstruction of the river will mimic its natural sinuosity and restore a continuous riparian and wetland edge. A riffle-pool sequence will support native fish, a sport fishery, and paddle sports. Fingers of the terraced natural river edge will extend into the district, merging urban and natural qualities. The proposed river terraces will be an important part of the district’s stormwater system that will reduce the volume and improve the quality of urban runoff and support the natural functions of the floodplain. These terraces will be part of a comprehensive system of flow reduction techniques used throughout the district, including porous pavements and green roofs, designed to reduce or eliminate the need for large, single-use stormwater detention and treatment facilities.

(Top) The need for a traditional piped stormwater system is reduced using natural technologies. Surface stormwater runoff is treated in permeable streets and stormwater planters. Green roofs provide detention, which is piped to sustain wetlands and riparian areas along the river.

(Bottom) Nearly one mile of the South Platte River will be restored as a functioning natural floodplain with multiple environmental and recreational benefits.

Los Angeles River Corridor - Revitalization and Transformation of Its Watershed

Master planning for the Los Angeles River corridor Illustrates how a multifunctional stormwater system conceived of at a site, community, and watershed scale can transform the river and the city. Naturalizing 36 miles of the Los Angeles River, now a concrete-lined channel as it passes through the city of Los Angeles, is only achievable by transforming stormwater management throughout the watershed. Transformation and multiple use of the river is possible only because of proposed multiple benefits that address issues of flood risk management, restoration of the river’s natural functions, revitalization of underserved communities, and the creation of new parks and open spaces. As principal river planners for the project, Wenk Associates worked closely with engineers and scientists to propose multiple functions and values for the river corridor and the river.

It is impossible to remove the concrete channel lining without changing the hydrology of the watershed to reduce the volume of flood flows, which is only possible if storm flows are reduced throughout the watershed. The revitalization master plan prompted multiple studies that will transform the river's tributaries, and green infrastructure practices will be implemented citywide. Naturalization of the river requires restoring the natural functions to the river and its tributaries and implementing green stormwater practices throughout the city. Without the added values and uses of community gathering, recreation, and leisure, a master plan based solely on “functioning natural systems, water conservation and reuse, and community implementation” would fail to gain broad community support.

(Above) The plan recommends storing flood flows outside of the river channel and treating stormwater discharges from large storm drains and tributary streams in existing highway rights-of-way and adjacent underused lands.

(Above) The plan recommends storing flood flows outside of the river channel and treating stormwater discharges from large storm drains and tributary streams in existing highway rights-of-way and adjacent underused lands.

What We’ve Learned

The last part of the Working Water shares what Wenk Associates has learned after observing our projects and built work over a period of many years. We hope that our insights will help in the design of more effective stormwater control systems.

Part three includes the following select sections:

Design professionals must demonstrate the marketability and economic benefits of green infrastructure Market-driven urban stormwater systems at a neighborhood or district scale are technically feasible, but the design professions are often limited by aversion to risk and have little incentive to innovate.

Multiple barriers limit project scale and opportunities for innovation

Existing public policy, outdated legal and financial systems, and ingrained professional practices often discourage or prohibit the implementation of larger-scale stormwater systems. Entrenched design standards and maintenance practices can limit innovations in system design and lessen how better maintenance and management practices could improve performance.

The Best Projects Are in the Future

In many ways it's a great time to be a landscape architect. Our profession has a great deal to contribute to addressing the environmental and social issues of our time, and many firms have demonstrated their value through significant built work. Many landscape architects are leading community scale projects that enhance natural and social systems, and multiple firms are involved with and often driving the massive reworking of coastal shoreline protection projects. In China, multiple cities are going through a dramatic transformation as part of the “sponge cities” initiative to organize their communities around expansive networks of green infrastructure that greatly enhances the function and livability of their cities.

Ian McHarg would be pleased; but I think he would also say there is so much more to do to deal with the environmental and social issues of today. It's up to the next generation of landscape architects to continue to implement his vision.

Print

Print Email

Email