Introduction to cost of production and its uses part 2

Part 2: Fixed costs

While variable costs can be influenced by the production volumes, “fixed” costs are generally the same each year regardless of volume. They are often considered basic necessities to produce goods or commodities and can be foundations from which the business operates.

Land is one of the most common examples of a basic necessity. Without land, crops cannot be grown, cattle grazed on pastures or buildings raised to farrow hogs and milk cows. More importantly, farm businesses simply cannot grow without adding land in some way, shape or form.

That is why farm property is so highly sought after. Acquisition of land is a challenge for every farm. The rate of renting or buying ground has continued to increase over the last few years, especially when it is highly productive or reasonably located to another interested farm. This raises the question of how much is too much for a basic necessity such as land?

Negotiations for land often begin with a focus on the highest yielding and most profitable crop to be grown. However, managers need to take into consideration of all the years the property will be farmed.

Table 1: Farm Profit/ Loss Example |

Year 1 (Corn) |

Year 2 (Soybeans) |

Year 3 (Corn) |

Year 4 (Soybeans) |

Year 5 (Corn) |

| Farm Revenue | $750 | $540 | $675 | $510 | $750 |

| Variable Costs (seed, fertilizer, chemicals, etc.) | -$350 | -$200 | -$350 | -$200 | -$350 |

| Fixed Costs (Farm Insurance, Real Estate Tax, etc.) | -$75 | -$75 | -$75 | -$75 | -$75 |

| Farm Profit/ Loss (Before rent) = | $325 | $265 | $250 | $235 | $325 |

| Rent Cost | -$250 | -$250 | -$250 | -$250 | -$250 |

| Farm Profit/ Loss (After rent) = | $75 | $15 | $0 | -$15 | $75 |

Table 1. illustrates an example of a farm for rent where the owner is asking $250 per acre every year. The contract is for five years on irrigated ground. The farm’s corn yield averages 200 bushels per acre on this type of ground and the market is offering $3.75 per bushel or $750 of expected income. After covering expenses and the rent payment, the farm plans to make a profit of $75 per acre in the first year. This contract agreement looks very favorable to both parties.

How appealing is the contract in the second year, when the operation rotates to a crop like soybeans? The average soybean yield is 60 bushels per acre and the market price is $9.00 per bushel for an expected income of $540 and profit of $15 per acre. Should the farm agree to take on the property? What if the corn yield in the third year drops to 180 bushels? Or the market price for soybeans falls to $8.50 per bushel in the fourth year? What if both yields and prices fall in the same year?

As the example illustrates, fixed costs do not carry the sharp swings of increases or decreases seen in some years that variable costs do, but they still have a significant impact on a farm business. Understanding how these affect the cost of production year after year is important, if a farm is to successfully and consistently reach its goals.

Depreciation is another type of Fixed Cost.

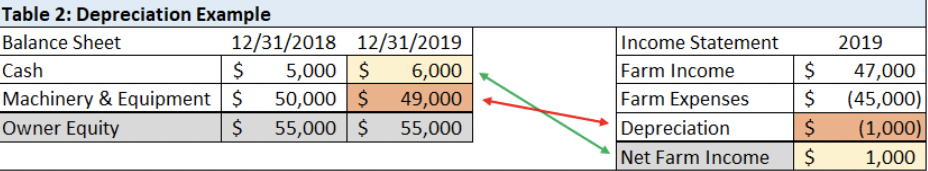

Depreciation is used routinely in evaluating profitability and is a helpful tool for farm managers. It can also be one of the most misunderstood and confusing topics for newer decision-makers, since it is not something you will find in the farm’s checkbook.

Specifically, we are speaking about “economic” depreciation, which is different than “taxable” depreciation, which will be covered in a later publication. Economic depreciation focuses on calculating the lost value of farm equipment, buildings, and even vehicles from age and use. This is important both from a profitability viewpoint and to the overall net worth of the farm business itself.

Think about a newly purchased skid steer on a livestock operation. At the time of its purchase, it was worth $10,000 and added this value to the overall net worth of the business. Used routinely throughout the year, it received regular maintenance and was repaired when any breakdowns occurred. At the end of the year, if the farm were to sell, they are told that it is worth only $9,000 to a potential buyer. How does this change in value impact the business?

The net worth of the business has declined by $1,000, even though the equipment is fully functional and considered in “like-new” condition. To offset this, the farm’s cost of production calculation includes the depreciation value ($1,000 per our example) in order to determine if enough revenue is being generated to cover this loss.

Depreciation also has an added benefit of assisting managers in deciding if a capital asset should be replaced. As they continue to decline in value from use and age, farm assets will eventually require greater amounts of repairs to keep them functional. By comparing these impacts to variable and fixed costs, depreciation helps managers to understand if they are maintaining or growing the overall profitability and net worth of their businesses. Making it a vital part of the farm’s cost of production.

This is part of a six-part article series from the MSU Extension Beginning Farmer DEMaND series. The DEMaND series is a line of publications designed to help beginning farmers learn about financial and business management strategies that will assist them in developing into the next managers and decision-makers on the farm. For more information, check out the DEMaND series homepage on the MSU Extension’s Farm Management webpage.

Print

Print Email

Email