Infectious Coryza could be a concern for poultry owners

Several states have experienced an increase in infectious coryza cases in poultry flocks this spring, understanding the disease is critical in preventing and treating it properly.

Infectious coryza typically referred to as coryza, is a specific respiratory disease of chickens caused by the bacteria Avibacterium paragallinarum. Do not confuse this disease with the term "coryza", historically used by old-time poultry producers for any respiratory disease of poultry. Early literature and common names of infectious coryza are roup, contagious contagious or infectious catarrh, cold and uncomplicated coryza. Infectious coryza poses a substantial poultry health and economic risk, as the disease causes poor growth in young birds, and a significant (ten to forty percent) drop in egg-laying. Due to the higher than normal incidence of infectious coryza in some parts of the country, please read and refer to the following information regarding the disease.

Infectious coryza can occur at any age, mature birds are generally more at risk, and the disease is often seen during a flock's peak egg-laying phase. Many cases are seen following some stressful event. In laying hens, this is commonly seen after hens are relocated, i.e. from a pullet house to a laying-hen house. The causative bacteria is endemic (naturally found) in certain areas, such as the southwest, but can appear anywhere that chickens are raised. Currently, flocks are having problems with this disease in Arizona and Pennsylvania.

Birds can become carriers without showing any outward signs of the disease, making infectious coryza very hard to control on farms that don't practice an "all in, all out" policy. The disease can be spread via aerosols, ingested feed or water, people and contaminated clothing and equipment.

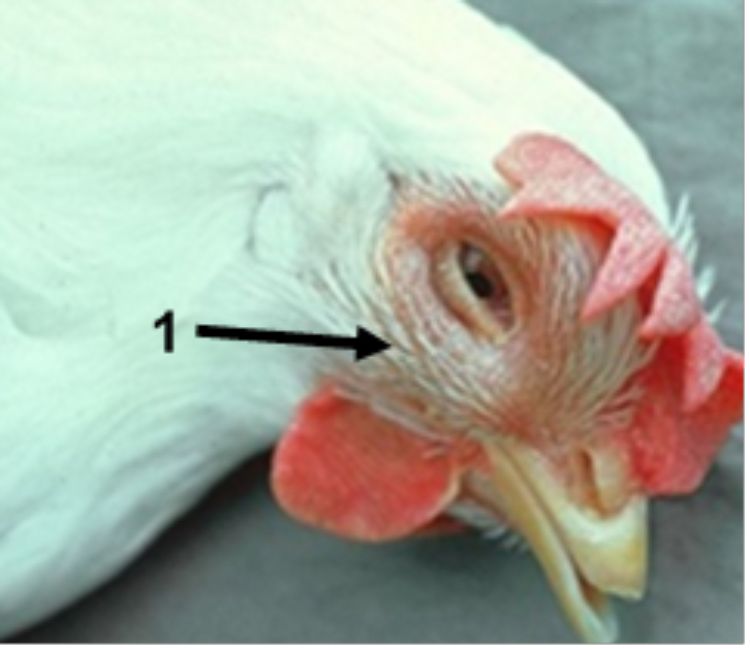

The most common and prominent symptoms of infectious coryza are edema or swelling of the face and conjunctivitis with nasal and ocular (eye) discharge. Swollen wattles may be present and are more commonly found in males. Infected chickens may also have common signs of upper respiratory diseases such as coughing and sneezing. Feed and water consumption may decrease and there will be a serious drop in egg-laying. Morality is generally low, but morbidity (loss of production either meat or egg and spread) is normally very high.

In areas where the disease is endemic, infected flocks are commonly depopulated to try and control the spread of the disease. After depopulation and infected birds are removed, premises should be cleaned, disinfected and allowed to sit idle for at least three weeks before adding new poultry. As with all diseases, the best prevention is practicing strict protocols.

For more information, contact Dr. Zac Williams, Poultry Extension Specialist, via email at Will3343@msu.edu, or by phone at 517-355-3855, or Dr. Mick Fulton, Poultry Extension Veterinarian, via email at fultonr@msu.edu, or by phone at 517-353-3701.

Print

Print Email

Email