How do I know if a pesticide is safe for bees? Five steps to protect bees from pesticides

This Article is offered in: English, Espanol

How to protect bees while managing pests.

A pesticide’s risk to bees depends on two factors: exposure and toxicity. Pesticide users can reduce risk to bees by limiting bee exposure to pesticides and by choosing products that are known to be less toxic to bees.

The effects of pesticides on bees can vary widely depending on the pesticide and how it is applied. Some pesticide applications can kill bees outright, some can cause sublethal harm such as impaired memory or reduced lifespan and some have no noticeable effect. Pesticide effects on bees can be complex, and some long-term or chronic effects on bees may be understudied or unknown, so we can’t guarantee with certainty that a pesticide is “bee safe.” People managing pests can take steps to reduce harm to bees by selecting pest-resistant plants, considering non-chemical options, practicing integrated pest management, choosing products known to be less toxic to bees, following the pesticide’s label and taking steps to reduce pesticide exposure of bees.

1. Select plants resistant to pests

Some plant species are more attractive to pests and susceptible to pest damage than others. Home gardeners and land managers can reduce the need to manage pests with pesticides by selecting pest-resistant varieties. These varieties may vary based on your geographic location, so you can reach out to your university extension or local gardening experts for advice on selecting plant varieties that are known to be resistant to pests. For example, Michigan State University Extension has an online article on selection, planting and care of trees and shrubs to avoid the need for pesticides.

2. Consider non-chemical options to manage pests

Some pests can be effectively managed without chemical pesticides. University extension educators/agents and online resources may recommend alternatives to pesticides for managing specific pests.

Integrated pest management (IPM) is an approach to pest management that considers all the pest control options available. For example, some pests can be effectively managed through prevention measures, cultural/sanitation practices, physical/mechanical barriers or biological controls. Pest control options vary widely depending on the pest and situation. In some situations, pests can be effectively controlled without the use of chemical pesticides.

3. Choose pesticides known to be less toxic to bees

There can be many considerations for selecting a pesticide, including risk to humans, effectiveness, cost and application method. Another consideration is the pesticide’s known harm to bees. The pesticide’s label reflects the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (U.S. EPA’s) pollinator risk assessment. To further minimize risk to bees, the label includes a combination of advisory environmental hazard statements and mandatory directions for use to protect bees. Some crops have additional restrictions on the label, such as limiting the number of applications during the bloom period, which reduces potential exposure to bees.

If you are considering multiple pesticide options, you can compare their known effects on bees by using the University of California Agriculture & Natural Resources Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program’s bee precaution ratings. The platform allows users to look up a pesticide by its common or trade name and the query will result in a rating of known harm to bees. You may be able to compare pesticide options and select a pesticide that is known to be less toxic to bees than the others. Once you have selected a pesticide to use, you must review the pesticide's label for instructions to protect bees and other important information. Some pesticide labels, especially newer labels, have rate and use-specific recommendations to protect pollinators that bee precaution ratings do not take into consideration.

The word “pesticides” is a broad term that includes many types of active ingredients to control pests. U.S. EPA lists types of pesticide ingredients, and the list includes insecticides, fungicides, herbicides and many other types of pesticides. Many insecticides are acutely toxic to bees. Other insecticides are chronically toxic to bees, resulting in sublethal harm. There is evidence that some fungicides are chronically toxic to bees or can work synergistically with insecticides in tank mixes to become acutely toxic. There is less evidence that most herbicides have chronic toxicity to bees, but they can have indirect effects by damaging plants that pollinators forage on. Some herbicide labels specify restrictions on their use around pollinator habitat. While pesticides are evaluated for risks to honey bees, they may not be evaluated for other bees or pollinating insects.

After-market adjuvants can harm pollinators, but unlike pesticides, their risks to pollinating insects are not evaluated. Whenever possible, reduce the application of pesticides around bee-attractive blooming plants and use care when using after-market adjuvants.

4. Follow the pesticide’s label

The pesticide label can include important bee precaution information. The United States Environmental Protection Agency evaluates pesticides for many risk factors, including risks to pollinators. Learn how the US EPA assesses risks to pollinators.

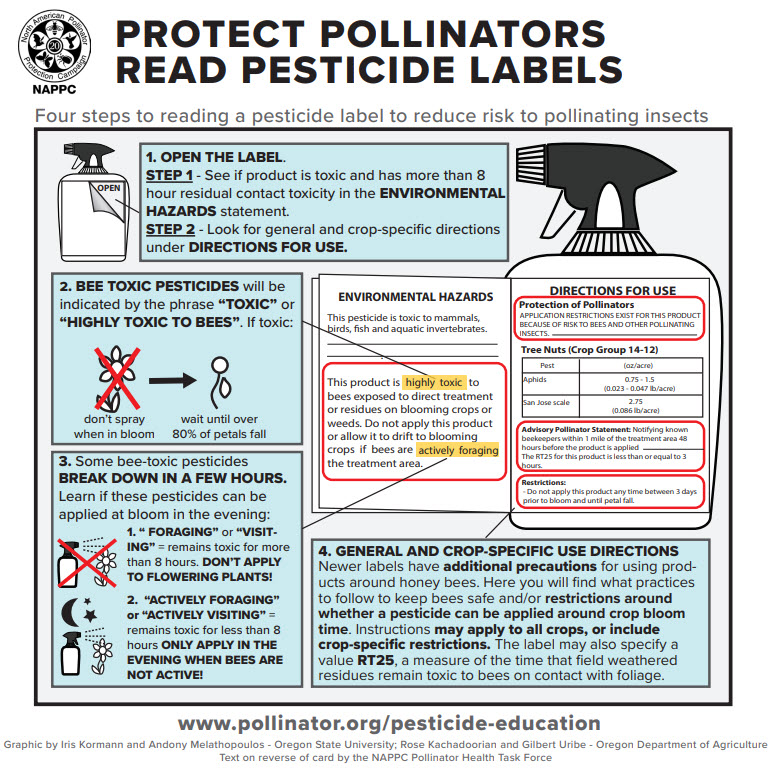

A pesticide must be applied according to its label. The Protect Pollinators: Read Pesticide Labels card has guidance on where to find bee precaution information on a pesticide label and a list of steps to minimize pesticide exposure to bees:

- Pesticides known to be harmful when exposed to bees are described as “highly toxic” or “toxic” to bees in the Environmental Hazards section of the pesticide label. Products that are “highly toxic” or “toxic” to bees should not be applied to flowering plants.

- If the label’s Environmental Hazards section states to not apply the product or allow it to drift to blooming crops if bees are foraging or visiting the treatment area, then applicators should not apply it to flowering plants. If it says to not apply the product or allow it to drift to blooming crops if bees are “actively foraging” or “actively visiting” the treatment area, then applicators should wait until evening when bees are not flying to apply the product to flowering plants.

- Additional bee precautionary statements may be found in the Directions for Use section of the pesticide label.

5. Take steps to reduce pesticide exposure to bees

A pesticide’s harm to bees can be reduced by limiting exposure. To protect bees, pesticide applicators should avoid applying pesticides to places where bees come into contact. Bee exposure to pesticides can be reduced by applying pesticides so they do not get into pollen, nectar, water and resins, nests or hives, or nesting materials. Applicators should also take care to avoid pesticide drift to these areas.

If allowed by the label, some pesticides with short residual times can be applied in the evening after bees stop flying. Applying a pesticide in the evening allows these pesticides to break down for several hours before bees will come into contact with it, however, applicators should be aware that evening pesticide applications may harm beneficial insects active at night, such as some moths.

For additional guidance, consult your state or tribe’s pollinator protection plan or reach out to university extension.

Resources

- Bee precaution pesticide ratings from the University of California Agriculture & Natural Resources Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program

- How We Assess Risks to Pollinators from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Protect Pollinators: Read Pesticide Labels card from the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign

- Michigan Pollinator Protection Plan Resources

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Crop Protection and Pest Management Program through the North Central IPM Center (2022-70006-38001).

This work is supported by the Crop Protection and Pest Management Program [grant no 2024-70006-43569] from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Thank you to the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development for securing funding from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for Michigan State University to implement strategies in the Michigan Managed Pollinator Protection Plan.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Print

Print Email

Email