Warning issued over 50 years ago still rings true: CDC renews attention to antibiotic resistance

Labeled an urgent health threat in 2013, antibiotic resistance has become one of the world's greatest challenges. What is drug resistance and how does it develop?

In an untidy hospital lab in London, Alexander Fleming accidentally discovered an infection-fighting agent that would change the course of history. Amidst a stack of forgotten bacteria-filled petridishes, Fleming found one sample with a fungus that had killed the surrounding germs. He was able to extract the mold and grow it, and he found that it could ward off many other types of bacteria as well. By the 1940s, that mold — eventually called penicillin — had become the first commercially available antibiotic.

Early in his studies, however, Fleming found that bacteria developed resistance whenever too little penicillin was used or if the drug wasn’t taken for an adequate amount of time. As he traveled the world making speeches about his discovery, Fleming alerted listeners about the need for proper use and dosage of the antibiotic.

That cautionary tale of drug resistance continues to be told with greater intensity and perhaps more emotion than ever before. Much of the recent attention was initiated last year, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a 114-page report titled “Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013," which some say has set off much-needed alarms.

Steven Solomon, director of the Office of Antimicrobial Resistance for the CDC, said the report is intended to educate the public in simple terms about the severity of antibiotic resistance, which has escalated in the past 10 to 15 years, largely because of a marked decline in new drug discoveries (see related story on page 22). With cases emerging of untreatable hospital-acquired infections, multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, and drug-resistant gonorrhea, Solomon said there is little doubt that society is on the verge of what is being called the “postantibiotic era.”

“There is a real risk that we’re going to get to the point where we are more commonly encountering resistant bacteria that cannot be treated with existing antibiotics,” he said. “We’re facing the prospect of returning to the world of 80 years ago and the nightmarish possibility of not being able to treat seriously ill people with infections.

“We’re already getting reports from clinicians that they have seen patients who, often after extended hospitalizations and who have had multiple infections and multiple courses of antibiotics, are now infected with bacteria that cannot be treated.”

Because there was a constant flow of new antibiotics developed between 1950 and 1980, many healthcare providers —including Solomon, who was in medical practice during part of that time — became complacent about antibiotic use, he said.

“I think there was a sense that we didn’t need to worry all that much about resistance because there was always a new antibiotic coming along that would take care of that resistant bacteria. For the first 30 or 40 years, that was largely true,” Solomon said. “Since the 1990s, however, there has been a significant decrease in the number of new antibiotics coming onto the market. The new drug pipeline is drying up.”

Antibiotics are the most commonly prescribed drugs in human medicine, but studies estimate that about a third to a half of their use is unnecessary or inappropriate. Antibiotic resistance develops naturally over time and cannot be prevented.

About 2 million people in the United States each year acquire serious bacterial infections that are resistant to one or more antibiotics.

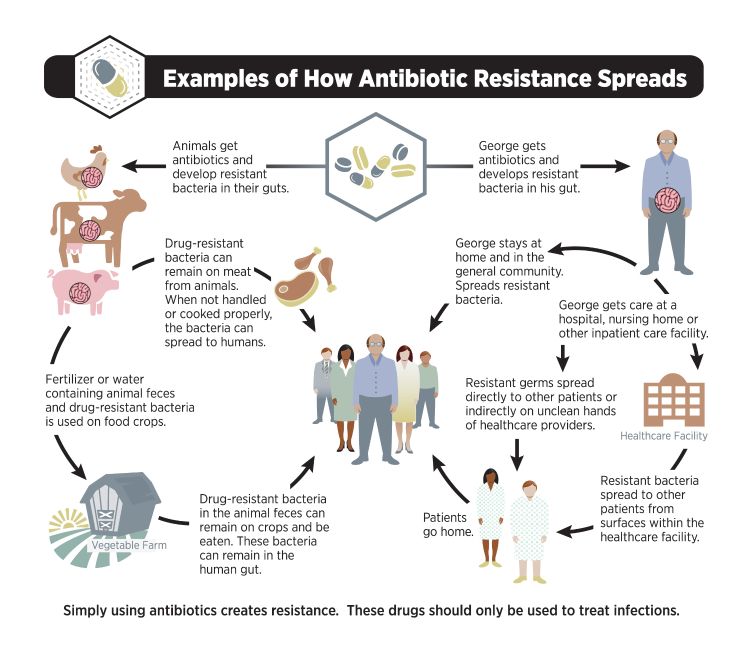

According to the CDC, the use of antibiotics is the single most important factor leading to antibiotic resistance around the world. In addition to use in human medicine, antibiotics are also commonly used in foodproducing animals to prevent, control and treat disease, and to promote growth and, in very small amounts (less than 0.5 percent of total usage), to treat plant crops against bacterial infections.

Because of the many factors contributing to its development, antibiotic resistance is a polarizing topic that has caused friction between industries and individuals. Experts warn, however, that there is no time to point fingers or place blame. Instead, they say the focus should be on raising awareness and, ultimately, finding solutions.

James Averill, state veterinarian in the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD) Animal Industry Division, said antibiotic resistance poses a major communication hurdle because of its scientific complexity.

“If you think you understand antimicrobial resistance and its impact, you haven’t begun to scratch the surface,” Averill said. “This is an extremely complex issue. It’s the whole relationship of us — as a world — that plays into this. It’s part of the reason why MDARD is involved in the One Health initiative.”

The foundation of One Health is that worldwide the health of humans is connected to the health of animals and the environment. It is often referred to when discussing antibiotic resistance because of its simplistic, unified message that all life is connected. It has also been the topic of National Institute of Animal Agriculture symposiums, which Solomon and Averill have both attended.

“I’ve become a big fan of the One Health approach,” Solomon said. “Antibiotics are being overused everywhere, so we all need to be more circumspect, and we need to be better stewards of antibiotics everywhere. It’s not about affixing blame, and it’s not saying this area is a problem versus this area. We have a problem in the United States and globally with using more antibiotics than we need to. We have not been protecting what is – as we now know and realize — a fairly precious and exhaustible resource.”

Despite mounting resistance concerns, experts agree that antibiotics should not be banned. The drugs have life-saving capabilities for both humans and animals, and they also help to keep the food supply safe. Engaging in dialogue has consequently become a top priority for many of the groups affected by antibiotic resistance.

For example, Averill led an MDARD-sponsored workshop in early 2013 with industry representatives who gathered to discuss the issue and learn more about new guidelines set by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the regulatory agency overseeing antibiotic use in livestock.

“During the workshop, what it really boiled down to was ‘What can we do to help assure that there is a good, valid producer-veterinarian relationship?’” he said. “And, that producers understand the importance of utilizing antibiotics prudently or judiciously because there really has been no new class of antibiotics brought onto the market for animal agriculture in 30-plus years.”

The Food Animal Committee from the Michigan Veterinarian Medical Association will continue to drive conversations and hold meetings on the topic with stakeholders. In the meantime, Averill said he is confident that the agriculture industry will rise to the occasion.

“I really see these recent changes and initiatives as an opportunity for agriculture to step up to the plate and demonstrate that we are using our antibiotics prudently and in a way to maintain animal health and well-being while making sure we have a safe, wholesome product for consumers,”Averill said.

Because a significant amount of meat consumed in the United States is imported, many have voiced concern that similar measures as those employed by the FDA need to be taken to keep the food supply safe here and in other countries as well.

Solomon is optimistic that strides are under way in the United States to help improve the antibiotic resistance situation.

“When bacteria are exposed to antibiotics, they inevitably take an evolutionary step toward developing resistance,” he said. “We can’t risk compromising the effectiveness of the antibiotics we have right now through overuse and inappropriate use. Any step that makes us more judicious in our use of antibiotics —whether it’s in human medicine, veterinary medicine or agriculture — is a step in the right direction, and we need to be moving toward better antibiotic use in all of those areas. At the same time, it shouldn’t have to be one sector against the other.”

For the past decade or so, antibiotic resistance has outpaced new drug development, a trend that experts agree must be reversed. The twofold solution, according to Solomon, is to work on the development of new antibiotics while at the same time taking steps to slow down the development of new resistance.

“We’re never going to stop resistance, but by slowing it down significantly we can give ourselves more time for development of new antibiotics,” Solomon added. “And that will be our solution.”

Print

Print Email

Email