Can the practice of mindfulness reduce unconscious racial bias?

Efforts to create inclusive and equitable settings may be strengthened by including the practice of mindfulness.

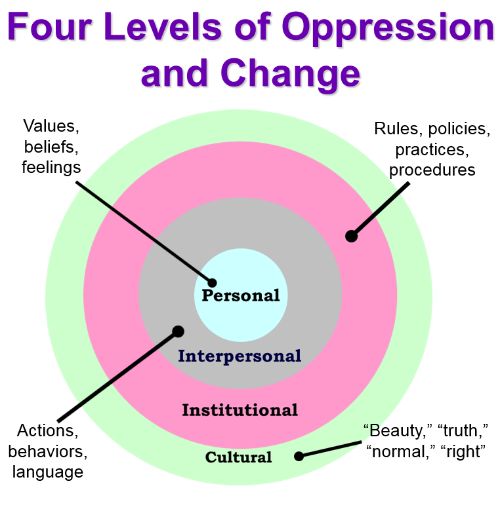

Addressing issues of bias and prejudice such as those related to race require us to learn about and work for change at four levels: personal, interpersonal, institutional and cultural. At the personal level, our feelings, attitudes and beliefs (some conscious and others unconscious) often impact our language and behaviors at the interpersonal level. This sometimes leads to unintentional (yet hurtful) behaviors such as microaggressions against people who are different than us based on race, gender, class, sexual orientation and other differences. The personal and interpersonal levels ultimately impact (and are impacted by) policies, procedures and practices at the institutional level of organizations. One example is the well-documented disparities in school discipline which unfairly target students of color and youth with disabilities for suspensions and expulsions. Another example is discriminatory practices in the U.S. labor market that favor white candidates for jobs over African Americans. These kinds of inequities come with great personal, emotional, social, political and economic costs to people and communities. They also interact within the larger background or societal climate at the cultural level which informs what people see as “normal,” “right” and “true.”

For those interested in working for positive change around issues of bias and prejudice, one place to start is to understand how unintentional bias works at the personal level to reinforce discrimination against some groups. Researchers at Harvard University developed an online tool to measure one’s level of implicit or hidden biases called the Implicit Association Test (IAT).

Research indicates that we all have a tendency to hold stereotypes and bits of inaccurate information stored in our brains about groups that are considered “out groups”—groups that tend to be stigmatized and marginalized in society such as African-Americans, gay people and those who are of higher weights. While explicit stereotypes are evaluations or judgments of people (or whole groups of people) that we are aware of and can report, implicit biases are attitudes or stereotypes that we hold but that are subconscious and outside of our awareness. These hidden biases are particularly problematic because we may act on our misguided stereotypes and attitudes in our interpersonal encounters without even being aware that we are doing so.

One way to address implicit bias is to learn more accurate information about the realities, histories and humanity of people and groups who continue to be targets of prejudice and discrimination. It’s also important to move away from denial or “colorblind” thinking and move toward what University of San Francisco legal scholar Rhonda Magee calls “ColorInsight.” Magee’s approach to addressing racial bias is unique because it includes the practice of mindfulness. Magee stresses the importance of Mindfulness-Based ColorInsight Practices which may be particularly relevant for police, educators, doctors and others who are interested in addressing ways that implicit biases may affect their work.

Formal and informal mindfulness practices invite us to actively and nonjudgmentally focus our attention on the present moment with openness, curiosity, flexibility and kindness. Practitioners of mindfulness learn to allow and experience their thoughts and feelings without getting attached to them or taking them too seriously. More than 35 years of research shows positive impacts of the regular practice of mindfulness on people’s overall health and wellbeing. Recent research out of Central Michigan University shows that the practice of mindfulness may also reduce implicit bias. Participants in the CMU study listened to a guided meditation before and after taking the Implicit Association Test. Results showed that listening to the guided meditation led to a reduction in race and age bias. In another study conducted by researchers at the University of Sussex, those who participated in a brief loving-kindness mindfulness meditation specifically directed toward a racial out-group reduced their racial bias toward that group.

While more research is needed about how mindfulness can reduce implicit bias over the long term, these studies show the promise of practicing mindfulness to reduce hidden assumptions and stereotypes. Part of the reason mindfulness practice is effective is that it helps us to slow ourselves down, pause, observe our thoughts and feelings, become more self-aware and make intentional choices about how we want to respond to challenging situations—rather than jumping to conclusions and automatically reacting in ways that we sometimes regret. This practice is powerfully illustrated in the following quote by Viktor Frankl, the well-known neurologist, psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor:

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and freedom.”

~ Viktor E. Frankl, (1905-1997)

In addition to operating at four levels, issues of racial bias are historic, current, systemic and complex – and a short article like this can’t begin to illuminate all that is necessary to explore the depth of these issues. Books such as Reproducing Racism: How Everyday Choices Lock in White Advantage and Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People can help deepen one’s understanding of unconscious racial bias. In addition, Michigan State University Extension offers resources and programs focused on diversity and multiculturalism including issues related to the four levels of oppression and change, power and privilege associated with race, gender, class, disabilities and sexual orientation, emotional resilience and on the practice of mindfulness.

Print

Print Email

Email