Beyond the land: How regenerative grazing improves farmer wellbeing

Did you know how a farmer manages their land could influence their wellbeing? It’s not just about happiness; it's also about feeling accomplished, connected and fulfilled with life.

In recent years, the concept of human wellbeing has expanded to include multiple factors like health, relationships, purpose, and positive emotions. As Alejandro Adler and Martin Seligman suggest, it’s about more than just feeling happy—it’s also about finding meaning, managing stress, and maintaining physical health. But what does this have to do with farming, livestock production and the stresses of farmers’ everyday life?

When it comes to regenerative grazing, often farmer wellbeing is an integrated goal alongside soil health and is therefore an emerging area of interest. This management approach prioritizes adaptive livestock management principles to support soil health and build on the relationship between livestock and grassland. Studies suggest that adopting regenerative grazing practices can positively influence farmers’ confidence in handling difficult situations, such as droughts, as noted by Barton and colleagues in a 2020 study. It can also strengthen social networks and learning among farmers, according to research by Carien De Villiers, and reshape the way ranchers interact with their land, enhancing their overall relationship with it, as highlighted by rangeland specialist Justin Derner.

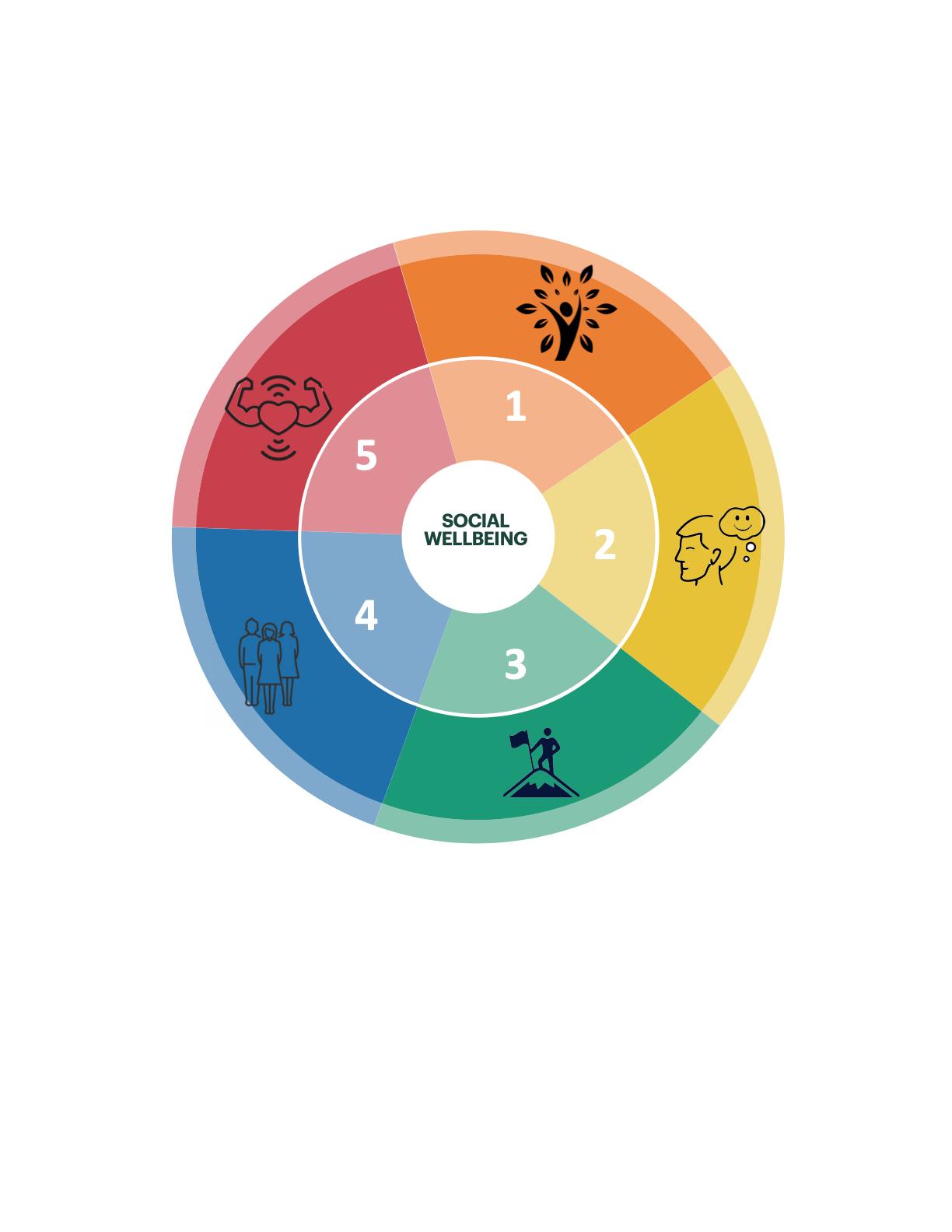

Despite these findings, there’s still a lot we don't know about how regenerative grazing affects farmers' wellbeing, especially in the Midwest. To bridge this gap, our study focused on pasture-based beef producers in Michigan, exploring their wellbeing across different grazing practices. We used a comprehensive framework that considers five key aspects of wellbeing: life satisfaction, hedonic (emotional) wellbeing, eudaimonic wellbeing (accomplishment, purpose and meaning), relational wellbeing (social connections) and physical wellbeing (health and financial conditions).

What we found: The state of farmers' wellbeing in Michigan

In our study, Michigan farmers scored highest in relational wellbeing, followed by eudaimonic (accomplishment, purpose and meaning) and physical wellbeing. This indicates that most farmers are satisfied with their social support, sense of accomplishment, health and finances. Interestingly, when asked which aspects of wellbeing mattered most to them, farmers consistently ranked relationships and purpose as their top priorities.

Overall, we found high levels of wellbeing across all groups of beef producers in Michigan. However, non-adaptive farmers—those sticking with traditional, more continuous practices—generally scored higher in all dimensions compared to those who are adapting or adopting new regenerative grazing techniques. The biggest differences were in life satisfaction, relational wellbeing.

Why these differences matter

You might wonder why these differences are worth exploring. Research suggests that individuals have a set point around which their wellbeing varies. Previous studies indicate that farmers' wellbeing typically ranges between 70–80% on wellbeing scales, which aligns with our findings for adaptive and adopting groups but not for the non-adaptive ones.

This discrepancy could be due to two possible scenarios. First, non-adaptive farmers’ higher scores might reflect a high state of control—they have adapted to their traditional practices and found a way to maintain their wellbeing over time. On the other hand, adaptive and adopting farmers could be in a transitional phase. Although we categorized farmers as adaptive if they had used such practices for at least five years, this period is relatively short in agriculture, and they may still be adjusting to the changes.

What does this mean for Michigan’s beef sector?

The key takeaway is that all groups of farmers in our study fall within a range typically associated with a healthy state of social wellbeing. While adopting new practices may influence social wellbeing, it does not significantly diminish it. This is encouraging news for the continued scaling-up of regenerative grazing practices in Michigan’s beef sector. By embracing these methods, farmers not only contribute to ecological health but also maintain, and potentially enhance, their own wellbeing.

The bottom line? Regenerative grazing has the potential to support both the land and the people managing it. More research is needed, but our findings offer a positive outlook for farmers considering this path.

Further information and resources to support farmers’ wellbeing are available at Michigan State University Extension Healthy Relationships and Farm Stress Resources.

Print

Print Email

Email