Avenues to reduce methane emissions from beef production: Understanding U.S. public support

The U.S. public prefers beef producers use seaweed to reduce emissions but publicly funded subsidies would not likely cover adoption costs.

Beef cattle are ruminants that produce methane (CH4) via enteric fermentation as a natural byproduct of their digestive process. Methane is a greenhouse gas (GHG). Estimates suggest 2.3% of U.S. GHG emissions can be attributed to enteric methane from beef production. Strategies to reduce enteric methane emissions are being researched and developed. However, there are currently no widespread economic incentives spurring U.S. beef producers to adopt these emerging strategies.

The market for beef products with climate or sustainability claims is niche. Thus, consumer demand alone is unlikely to generate necessary market incentives to reduce enteric methane emissions on a large scale. Consequently, several countries have begun exploring policy measures to reduce emissions from cattle. For example, Denmark subsidized the use of feed additive 3-Nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP), commercially marketed as Bovaer. 3-NOP has been approved for use in U.S. dairy production, but approval in U.S. beef production is pending. Other proposed strategies include feeding seaweed in diets, genetically selecting cattle that emit less methane, and shortening the lifespan of cattle by having them spend more time in the feedlot.

A nationally representative survey was conducted in November 2023 to determine what strategies the U.S. public prefers beef producers adopt to reduce enteric methane emissions. U.S. public support for mandating or subsidizing U.S. beef producers to reduce emissions was additionally quantified. In total, 2,288 usable responses were collected.

Seaweed reigns supreme

Seven potential strategies were analyzed, focusing on the feedlot stage of beef production. These include: (1) clone cattle that emit less methane, (2) feed cattle seaweed, (3) feed cattle 3-NOP, (4) genetically select cattle that emit less methane, (5) have cattle spend more time in the feedlot, (6) let the U.S. beef industry decide how to reduce emissions, and (7) let the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) decide how to reduce emissions. Cloning has not been widely considered to reduce emissions. However, it was included to provide a “base” category for comparison given the public’s distaste for the practice. Additionally, a subset of respondents received extra information about 3-NOP, including the projected methane reduction and that it is currently approved in the European Union.

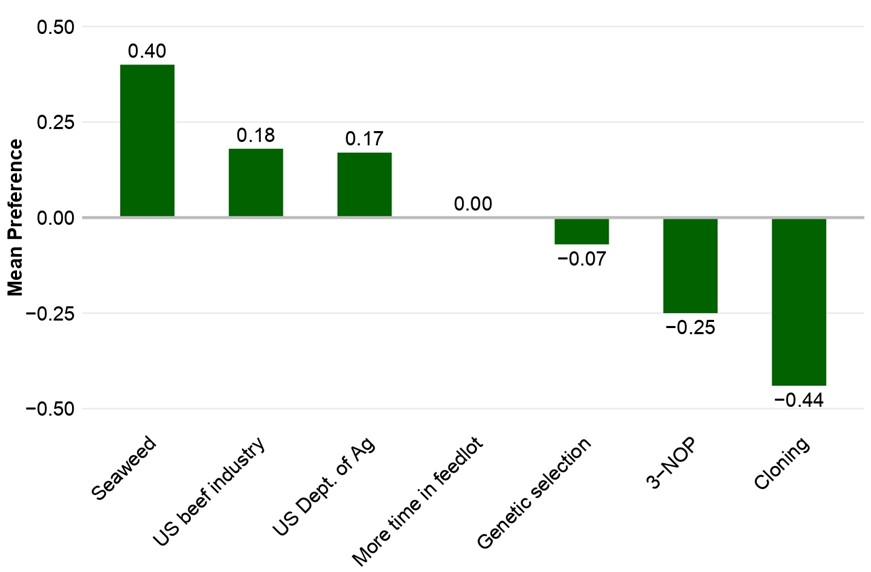

Survey respondents were presented with a series of questions that included different combinations of four of the seven strategies. For each combination, they were asked to select their most and least preferred strategy. Figure 1 illustrates that more time in the feedlot is a “neutral” strategy, with the same percentage of respondents considering it a most-preferred strategy as those considering it a least-preferred strategy. Seaweed is far less balanced, as 40% more considered this strategy most preferred as compared to least preferred. Conversely, 44% more considered cloning least preferred as compared to most preferred. Letting the U.S. beef industry or the USDA decide how to reduce emissions are ranked second and third, so the public desires some level of freedom for producers and agricultural leaders to make decisions.

Figure 1. Mean preference for strategies to reduce emissions from beef production

Meager policy support from the U.S. public

Half of the survey respondents were asked if they would vote in favor of mandating beef producers to adopt one of the strategies. Support for this initial mandate question varies, as summarized in Table 1. Feeding seaweed obtained the greatest share of public support (57%), followed by 3-NOP when extra information is provided (51%). Receiving the extra information has a notable impact on respondents’ support for a 3-NOP mandate, as the subset of respondents who did not receive extra information showed a much smaller share of support (29%).

Mandates create market inefficiencies that lead to price increases for consumers. If respondents answered yes to the initial mandate question, they were then asked if they would still vote in favor of mandating producers if it increased beef prices. Support for each strategy declined (by an average of 12.5 percentage points across strategies) for the mandate follow-up question. In fact, none of the strategies received over half of the public support. This highlights a disconnect between public support for producer mandates and their potential economic impact.

Half of the survey respondents (who did not receive the mandate questions) were asked if they would subsidize beef producers to adopt one of the strategies. Approximately 58% indicated they would vote in favor of a seaweed subsidy, followed by 3-NOP when extra information was provided (51%) and genetic selection (43%).

Table 1. Share of survey respondents who would vote yes for proposed policies

|

Strategy |

Mandate (Initial question) |

Mandate (After asking price increase follow-up question) |

Subsidy |

|

3-NOP |

29% |

22% |

27% |

|

3-NOP (Extra Information) |

51% |

37% |

51% |

|

Cloning |

35% |

28% |

19% |

|

Genetic Selection |

43% |

25% |

43% |

|

More Time Feedlot |

44% |

30% |

35% |

|

Seaweed |

57% |

42% |

58% |

Note: Letting the beef industry and USDA decide how to reduce emissions were both excluded from this portion of the study given their inability to be mandated or subsidized.

Adoption unlikely given estimated support

Table 1 suggests the U.S. public prefers subsidies over mandates that could increase beef prices. Yet, subsidies likewise have their own economic implications. In this case, U.S. taxpayers foot the bill. Those who answered yes to the initial subsidy question were then asked if they would still vote in favor of the subsidy if it paid producers a certain amount per head for adopting the strategy. The presented amounts ranged from $28/head to $112/head. Respondents were also presented with the potential annual government spending that could result from implementing the subsidy.

If respondents answered yes to the initially proposed subsidy level, they were presented with a follow-up question that doubled the amount, ranging from $56/head to $224/head. If they answered no to the initially proposed subsidy level, they were presented with a follow-up question that halved the amount, ranging from $14/head to $56/head. Table 2 summarizes the average estimated subsidy for each strategy.

Table 2. Estimated subsidies for emissions-reduction strategies

|

Strategy |

Estimated Subsidy ($/head) |

|

3-NOP |

$30.55 |

|

3-NOP (Extra Information) |

$57.66 |

|

Cloning |

$20.17 |

|

Seaweed |

$64.22 |

|

Genetic Selection |

$47.90 |

|

Feedlot |

$44.37 |

Note: These estimates also account for respondents who did not support the subsidy (meaning a support level of $0/head).

The largest estimated subsidy is for seaweed at $64.22/head. When this study was conducted, the average live weight of slaughtered cattle was 1,390 pounds. Thus, the estimated seaweed subsidy would be roughly $4.62/cwt. Estimates suggest feeding seaweed to cattle could cost 80¢/head/day, or $146/head ($10.50/cwt) assuming cattle are in the feedlot for six months. The estimated subsidy ($64.22/head) would not cover the cost of implementing seaweed into diets ($146/head).

For 3-NOP with the extra information, the estimated subsidy is $57.66/head ($4.15/cwt). At a 3-NOP cost of 25 cents/head/day, this would result in costs of $45.63/head ($3.28/cwt). The estimated subsidy would cover the cost of the additive ($4.15/cwt > $3.28/cwt). However, covering the cost of the product is not enough to spur producer adoption on average (Luke & Tonsor, 2024). In fact, producers require a larger incentive if it comes via a government subsidy as compared to a processor premium.

At a cost of 25 cents/head/day, the average small producer (who sells fewer than 2000 head per year) would need a subsidy of $5.29/cwt to adopt 3-NOP; the average large producer (who sells 2000 head or more per year) would need a subsidy of $3.38/cwt. Hence, the average small producer would be unlikely to adopt 3-NOP at this level, whereas the average large producer would be more likely. Large producers have more cattle to market, so funds flowing to large producers would far surpass those to small producers. This begs the question: Would the U.S. public offer the same level of support for subsidizing beef producers to reduce emissions if the majority goes to large operations?

Please note that details of the full study are available here. Jaime Luke is an assistant professor in the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics at Michigan State University. Glynn Tonsor is a professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Kansas State University. This information is for educational purposes only. Reference to commercial products or trade names does not imply endorsement by MSU Extension or bias against those not mentioned.

Print

Print Email

Email